- Copyright

- Brief Table of Contents

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- About this Book

- About the Author

- About the Cover Illustration

- Part 1. Introduction

- Part 2. Core Idris

- Chapter 3. Interactive development with types

- Chapter 4. User-defined data types

- Chapter 5. Interactive programs: input and output processing

- Chapter 6. Programming with first-class types

- Chapter 7. Interfaces: using constrained generic types

- Chapter 8. Equality: expressing relationships between data

- Chapter 9. Predicates: expressing assumptions and contracts in types

- Chapter 10. Views: extending pattern matching

- Part 3. Idris and the real world

- Appendix A. Installing Idris and editor modes

- Appendix B. Interactive editing commands

- Appendix C. REPL commands

- Appendix D. Further reading

- Appendix

- Appendix

- Index

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Listings

Type-Driven Development with Idris

Edwin Brady

Copyright

For online information and ordering of this and other Manning books, please visit www.manning.com. The publisher offers discounts on this book when ordered in quantity. For more information, please contact

Special Sales Department Manning Publications Co. 20 Baldwin Road PO Box 761 Shelter Island, NY 11964 Email: orders@manning.com

©2017 by Manning Publications Co. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in the book, and Manning Publications was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial caps or all caps.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, it is Manning’s policy to have the books we publish printed on acid-free paper, and we exert our best efforts to that end. Recognizing also our responsibility to conserve the resources of our planet, Manning books are printed on paper that is at least 15 percent recycled and processed without the use of elemental chlorine.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, it is Manning’s policy to have the books we publish printed on acid-free paper, and we exert our best efforts to that end. Recognizing also our responsibility to conserve the resources of our planet, Manning books are printed on paper that is at least 15 percent recycled and processed without the use of elemental chlorine.

| Manning Publications Co. 20 Baldwin Road PO Box 761 Shelter Island, NY 11964 |

Development editor: Dan Maharry Review editor: Aleksandar Dragosavljević Technical development editor: Andrew Gibson Project editor: Kevin Sullivan Copyeditor: Andy Carroll Proofreader: Katie Tennant Technical proofreaders: Arnaud Bailly, Nicolas Biri Typesetter: Dottie Marsico Cover designer: Marija Tudor

ISBN 9781617293023

Printed in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 – EBM – 22 21 20 19 18 17

Brief Table of Contents

Chapter 3. Interactive development with types

Chapter 4. User-defined data types

Chapter 5. Interactive programs: input and output processing

Chapter 6. Programming with first-class types

Chapter 7. Interfaces: using constrained generic types

Chapter 8. Equality: expressing relationships between data

Chapter 9. Predicates: expressing assumptions and contracts in types

Chapter 11. Streams and processes: working with infinite data

Chapter 12. Writing programs with state

Chapter 13. State machines: verifying protocols in types

Chapter 14. Dependent state machines: handling feedback and errors

Appendix A. Installing Idris and editor modes

Table of Contents

1.2. Introducing type-driven development

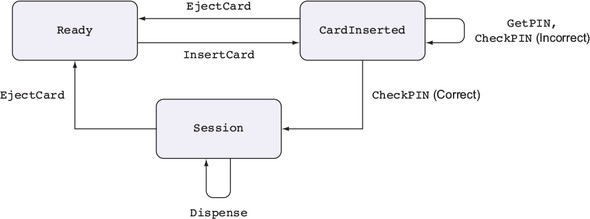

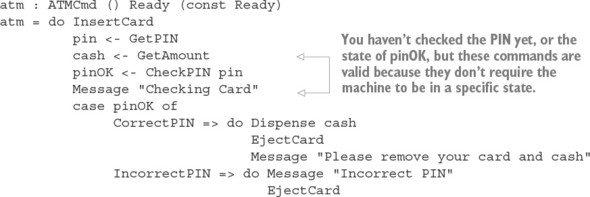

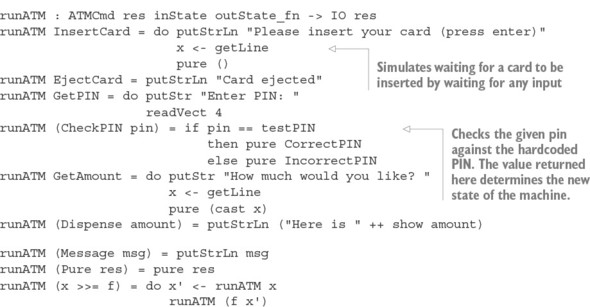

1.2.2. An automated teller machine

1.2.4. Type, define, refine: the process of type-driven development

1.3. Pure functional programming

1.3.1. Purity and referential transparency

1.4.1. The interactive environment

1.4.3. Compiling and running Idris programs

Chapter 2. Getting started with Idris

2.1.1. Numeric types and values

2.2. Functions: the building blocks of Idris programs

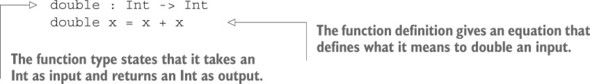

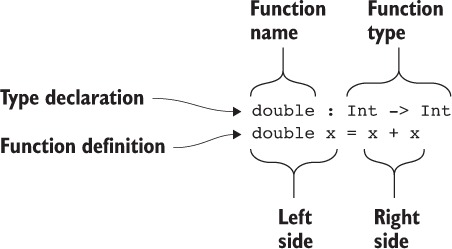

2.2.1. Function types and definitions

2.2.2. Partially applying functions

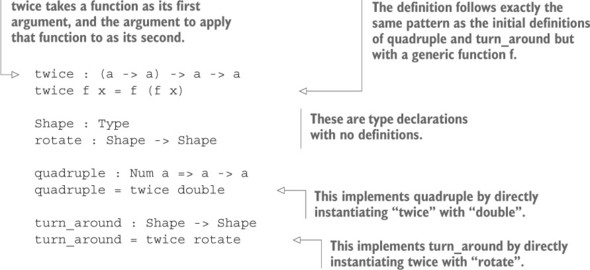

2.2.3. Writing generic functions: variables in types

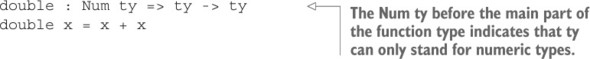

2.2.4. Writing generic functions with constrained types

Chapter 3. Interactive development with types

3.1. Interactive editing in Atom

3.1.1. Interactive command summary

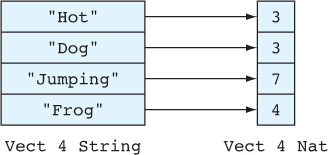

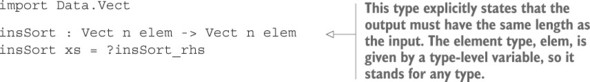

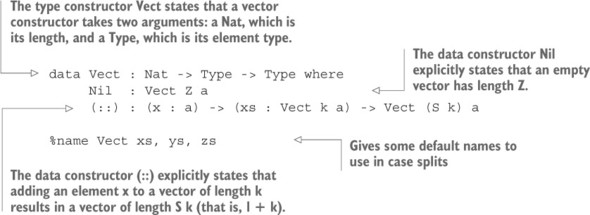

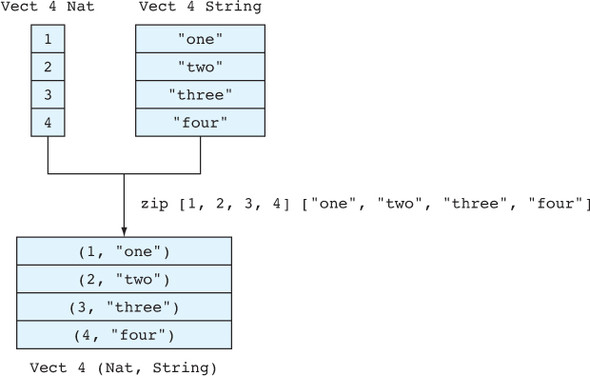

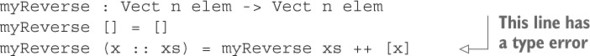

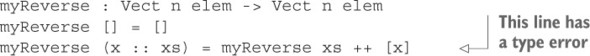

3.2. Adding precision to types: working with vectors

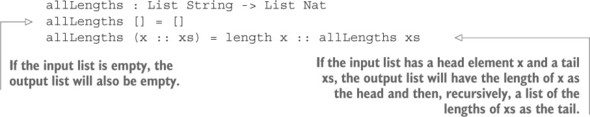

3.2.1. Refining the type of allLengths

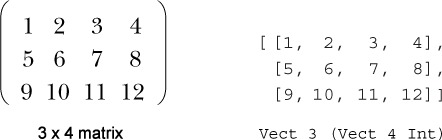

3.3. Example: type-driven development of matrix functions

3.4. Implicit arguments: type-level variables

3.4.1. The need for implicit arguments

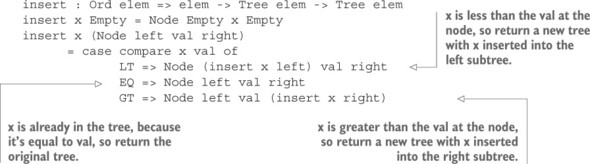

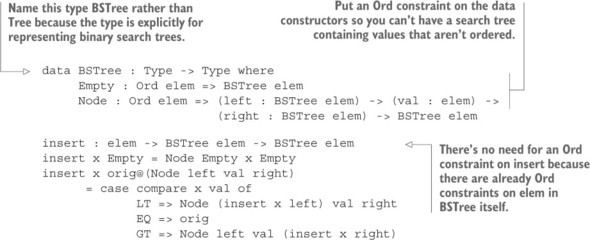

Chapter 4. User-defined data types

4.2. Defining dependent data types

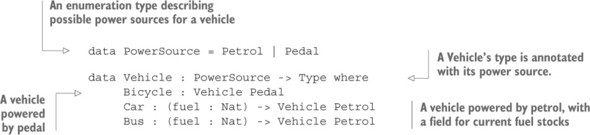

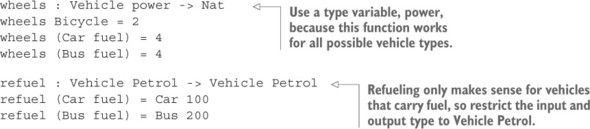

4.2.1. A first example: classifying vehicles by power source

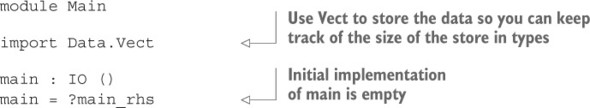

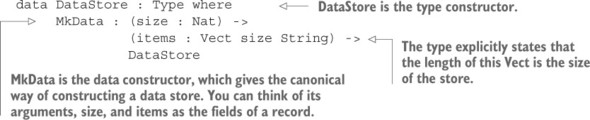

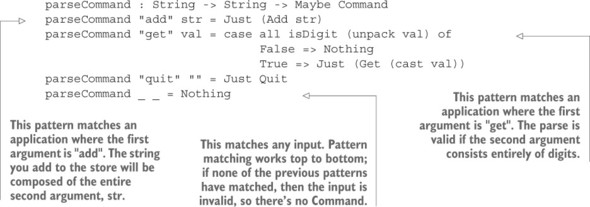

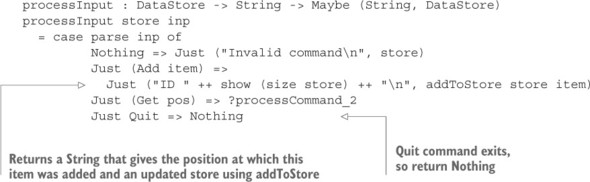

4.3. Type-driven implementation of an interactive data store

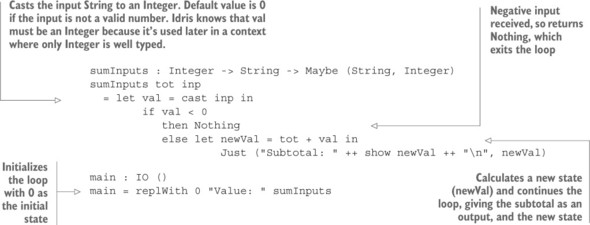

4.3.2. Interactively maintaining state in main

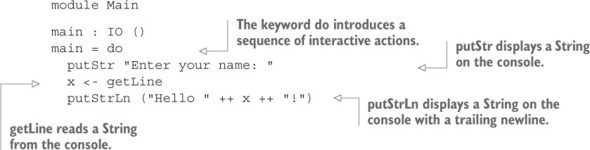

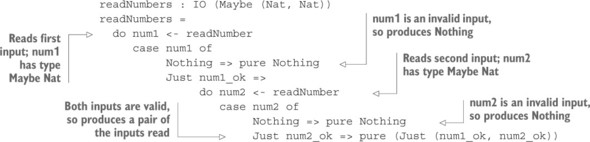

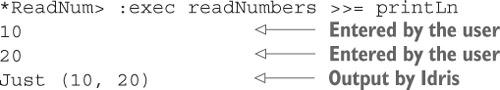

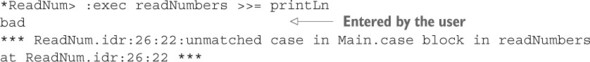

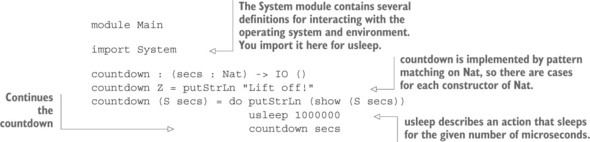

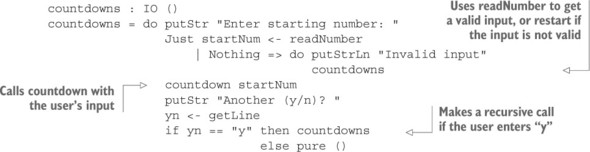

Chapter 5. Interactive programs: input and output processing

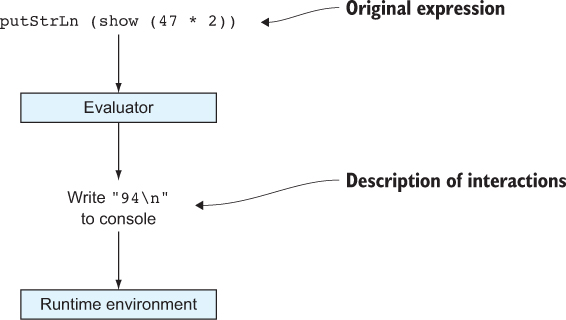

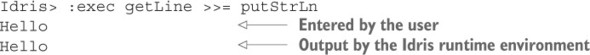

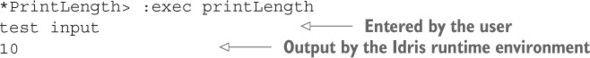

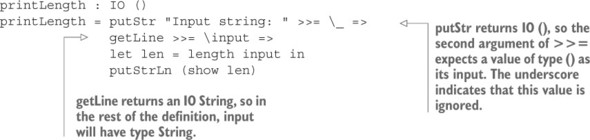

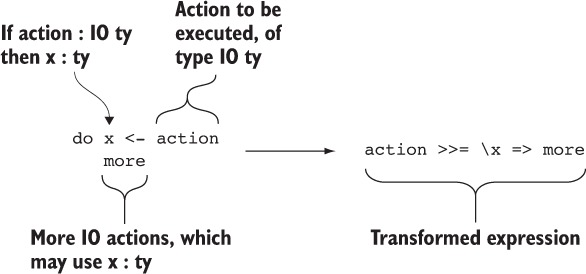

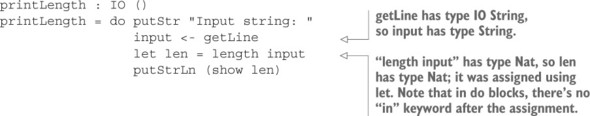

5.1. Interactive programming with IO

5.1.1. Evaluating and executing interactive programs

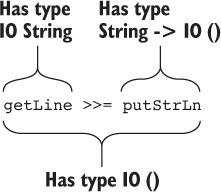

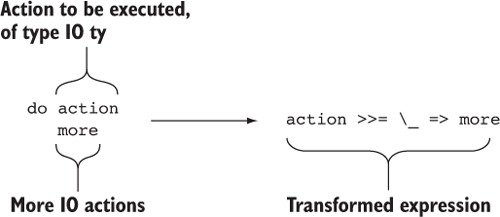

5.2. Interactive programs and control flow

5.2.1. Producing pure values in interactive definitions

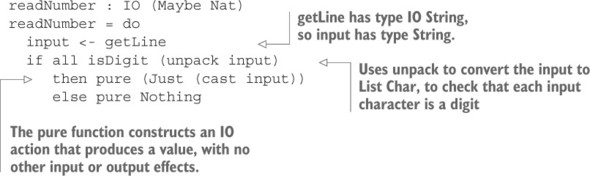

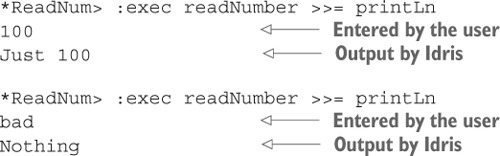

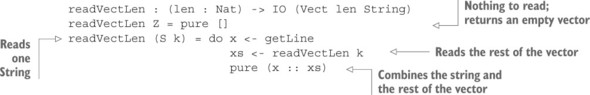

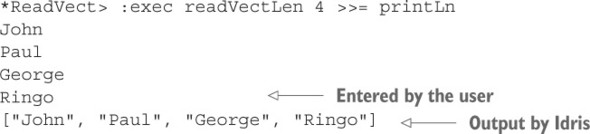

5.3. Reading and validating dependent types

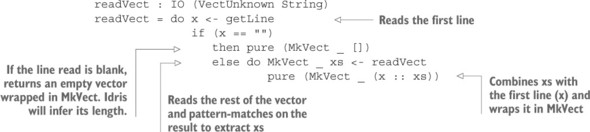

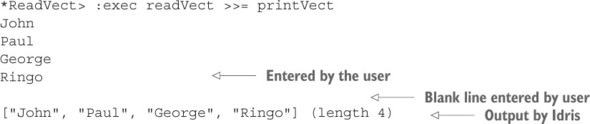

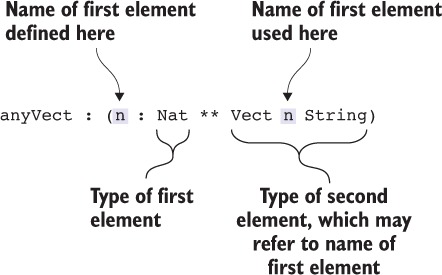

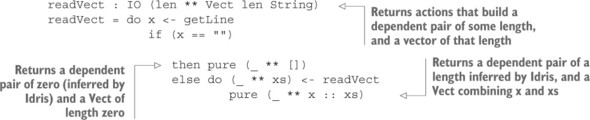

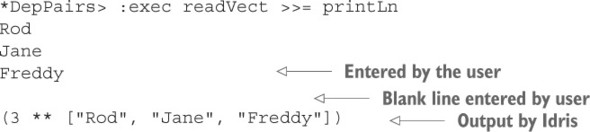

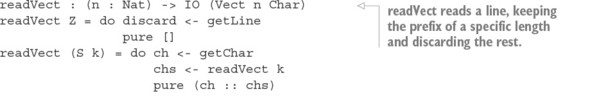

5.3.1. Reading a Vect from the console

Chapter 6. Programming with first-class types

6.1. Type-level functions: calculating types

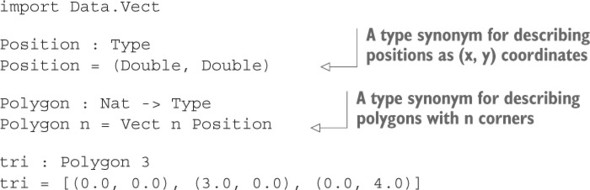

6.1.1. Type synonyms: giving informative names to complex types

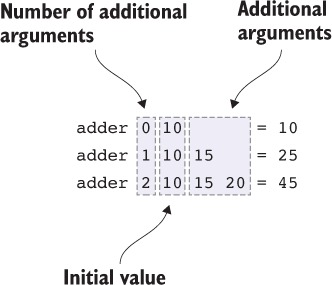

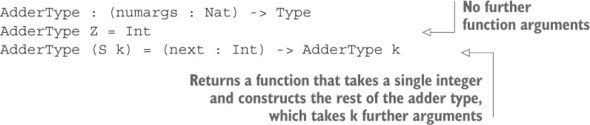

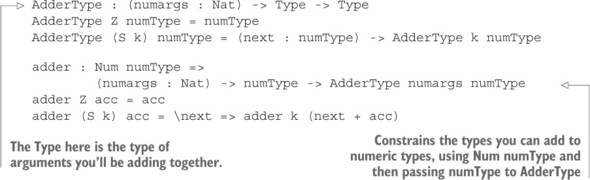

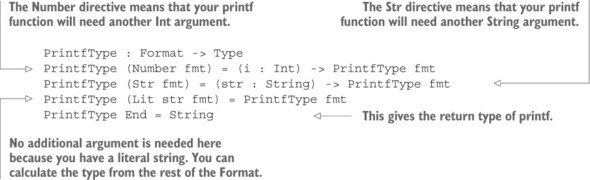

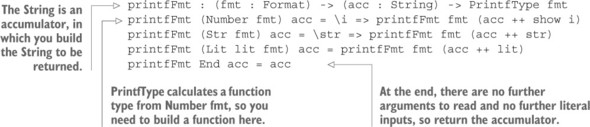

6.2. Defining functions with variable numbers of arguments

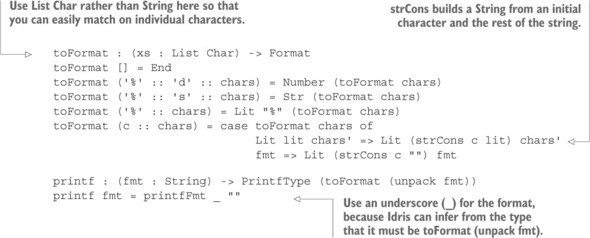

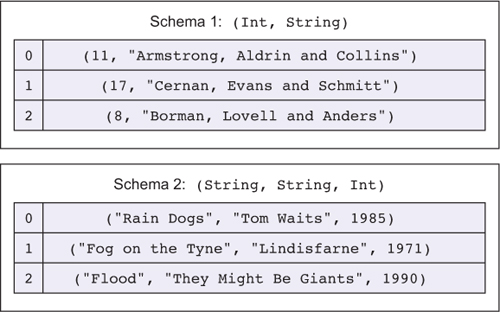

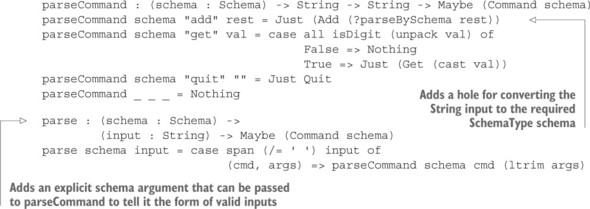

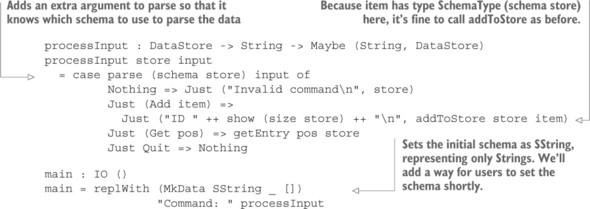

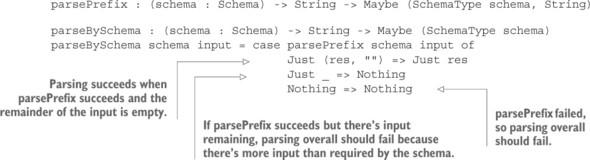

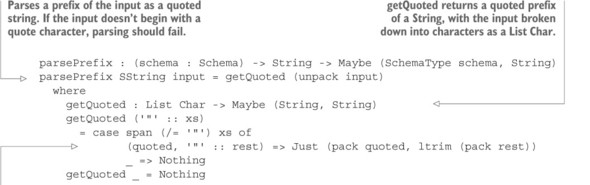

6.3. Enhancing the interactive data store with schemas

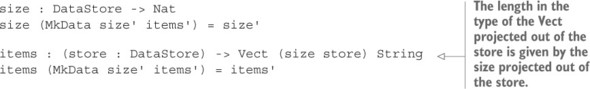

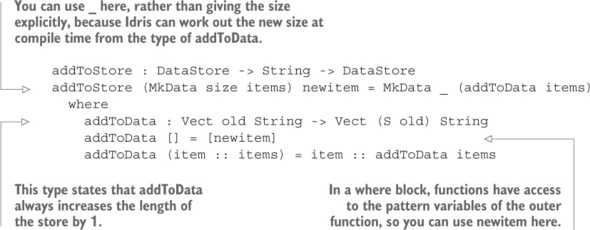

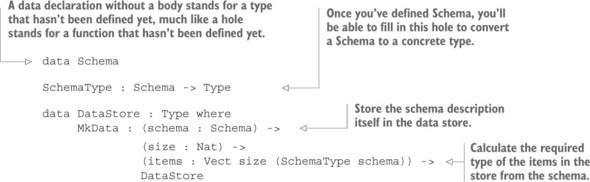

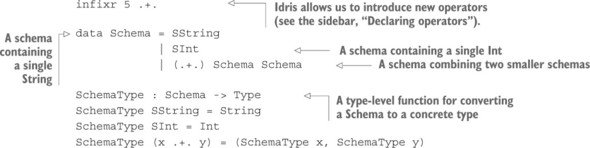

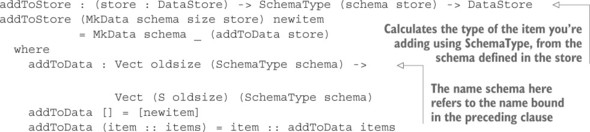

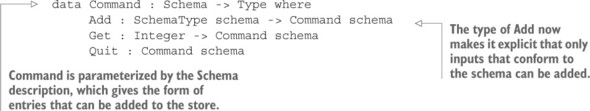

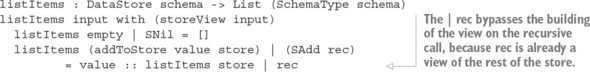

6.3.1. Refining the DataStore type

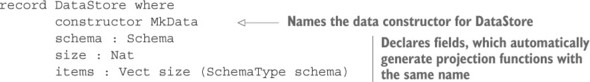

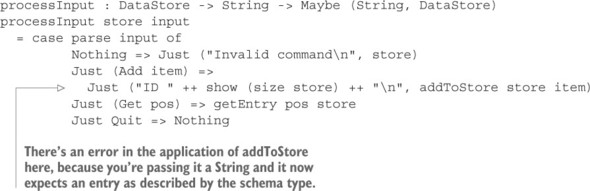

6.3.2. Using a record for the DataStore

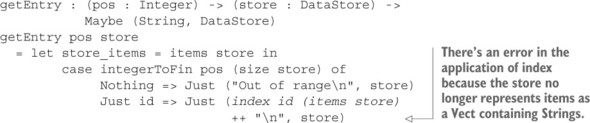

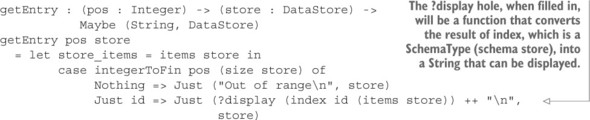

6.3.3. Correcting compilation errors using holes

6.3.4. Displaying entries in the store

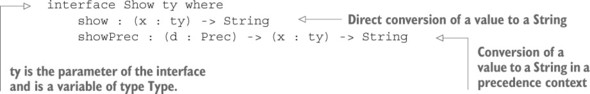

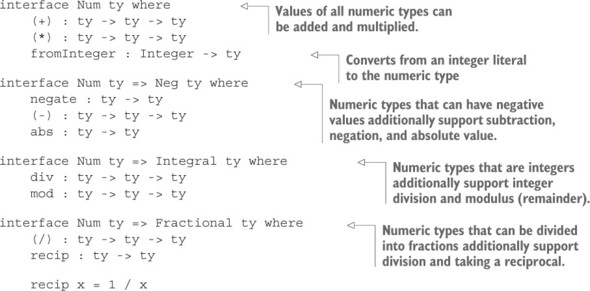

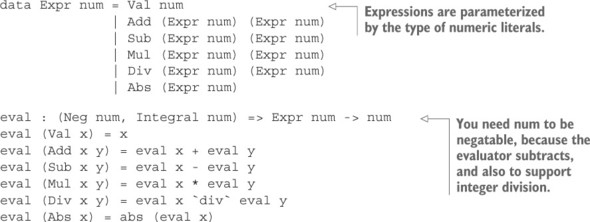

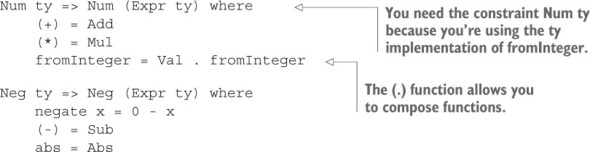

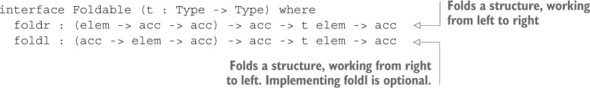

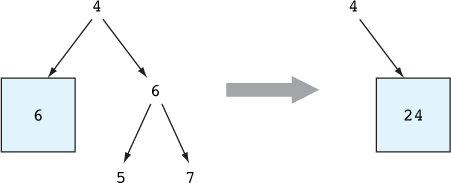

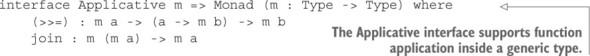

Chapter 7. Interfaces: using constrained generic types

7.1. Generic comparisons with Eq and Ord

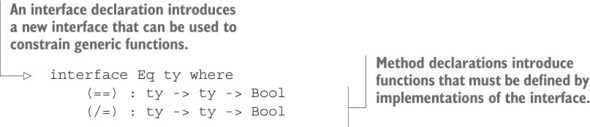

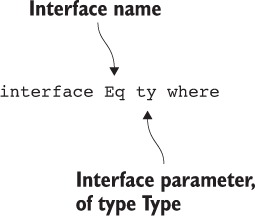

7.1.1. Testing for equality with Eq

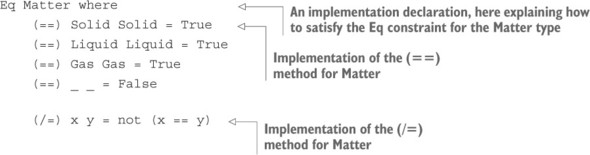

7.1.2. Defining the Eq constraint using interfaces and implementations

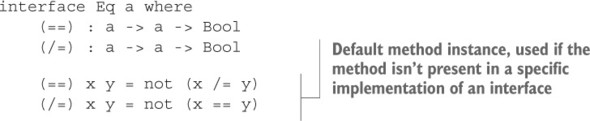

7.1.3. Default method definitions

7.2. Interfaces defined in the Prelude

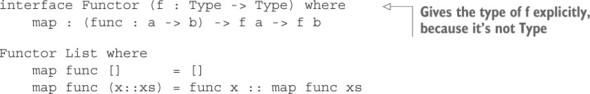

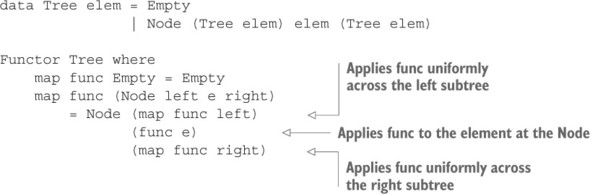

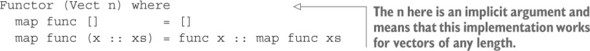

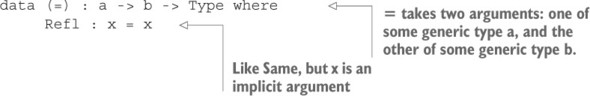

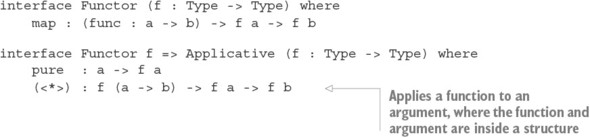

7.3. Interfaces parameterized by Type -> Type

7.3.1. Applying a function across a structure with Functor

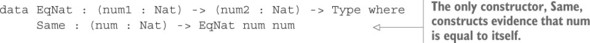

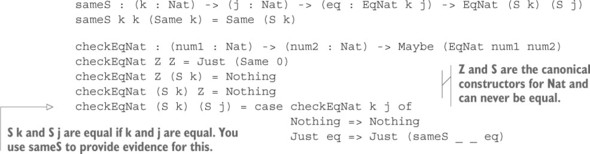

Chapter 8. Equality: expressing relationships between data

8.1. Guaranteeing equivalence of data with equality types

8.1.1. Implementing exactLength, first attempt

8.1.2. Expressing equality of Nats as a type

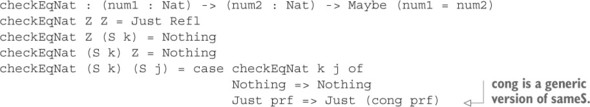

8.1.3. Testing for equality of Nats

8.1.4. Functions as proofs: manipulating equalities

8.2. Equality in practice: types and reasoning

8.2.2. Type checking and evaluation

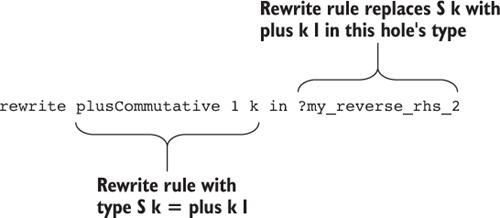

8.2.3. The rewrite construct: rewriting a type using equality

8.3. The empty type and decidability

8.3.1. Void: a type with no values

Chapter 9. Predicates: expressing assumptions and contracts in types

9.1. Membership tests: the Elem predicate

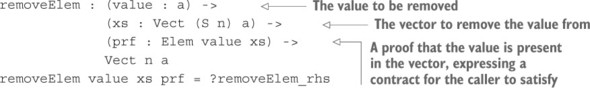

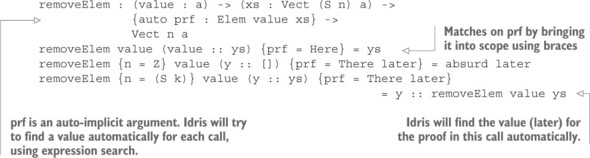

9.1.1. Removing an element from a Vect

9.1.2. The Elem type: guaranteeing a value is in a vector

9.1.3. Removing an element from a Vect: types as contracts

9.1.4. auto-implicit arguments: automatically constructing proofs

9.1.5. Decidable predicates: deciding membership of a vector

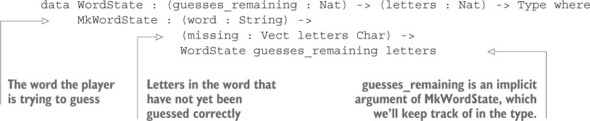

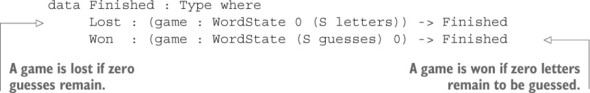

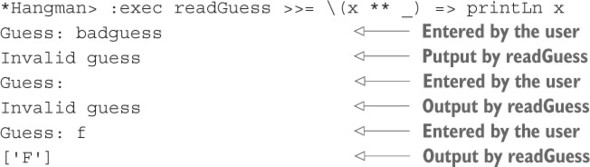

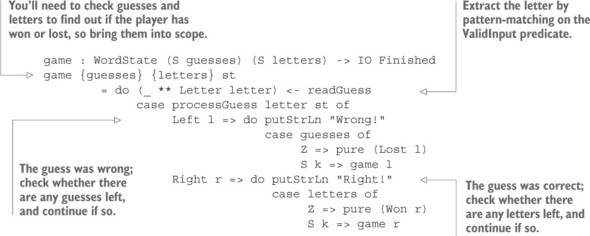

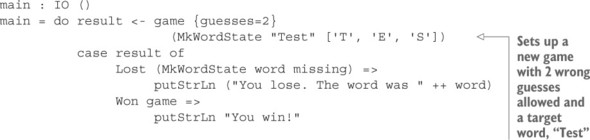

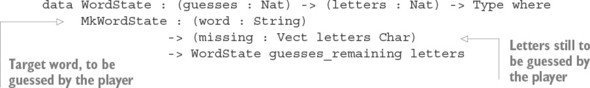

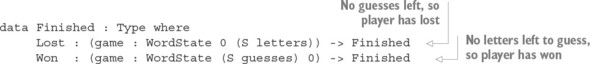

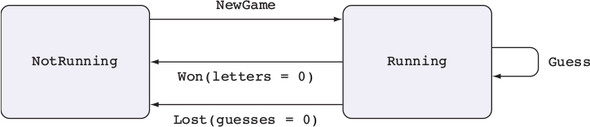

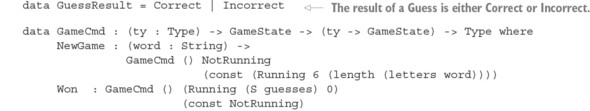

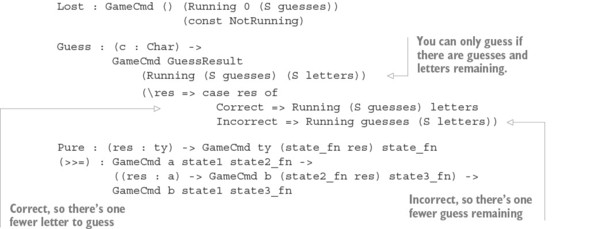

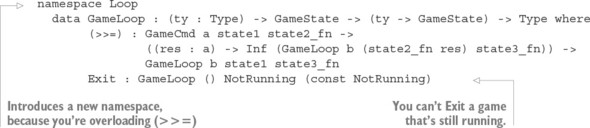

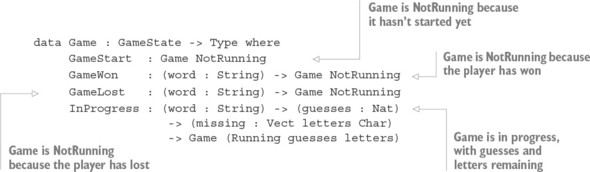

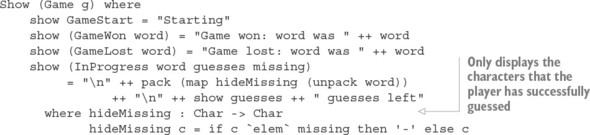

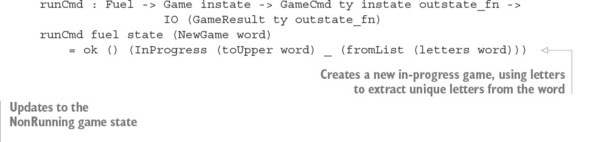

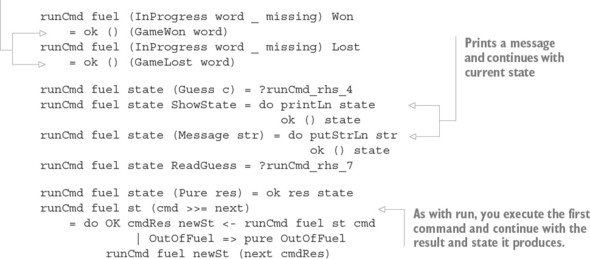

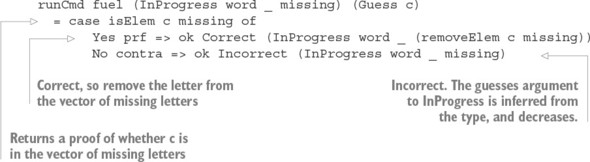

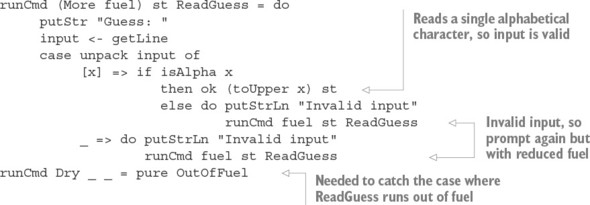

9.2. Expressing program state in types: a guessing game

9.2.1. Representing the game’s state

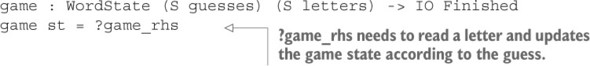

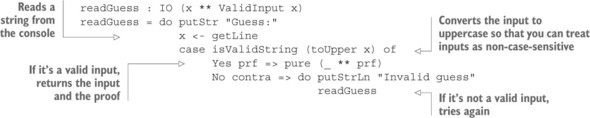

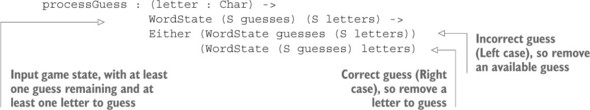

9.2.2. A top-level game function

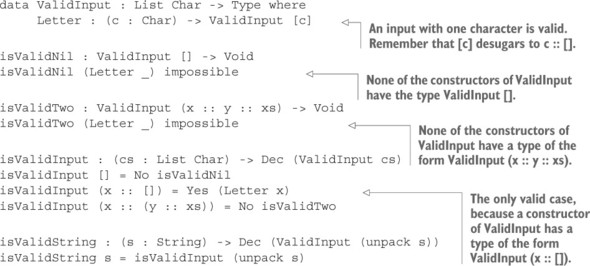

9.2.3. A predicate for validating user input: ValidInput

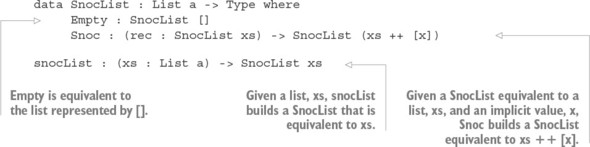

Chapter 10. Views: extending pattern matching

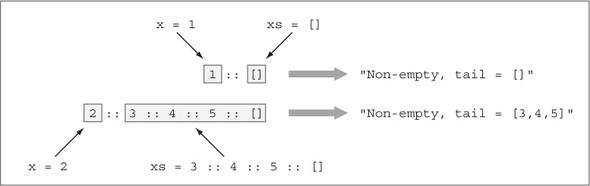

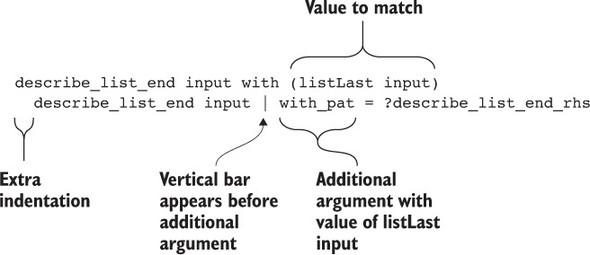

10.1. Defining and using views

10.1.1. Matching the last item in a list

10.1.2. Building views: covering functions

10.1.3. with blocks: syntax for extended pattern matching

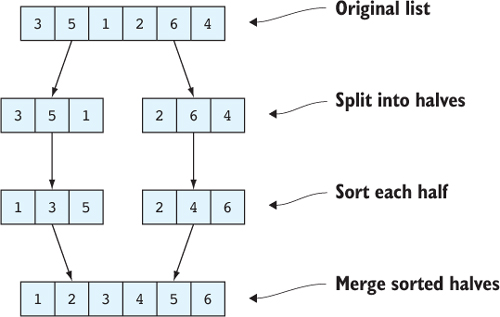

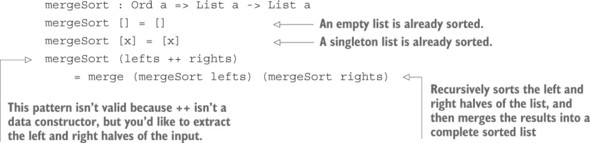

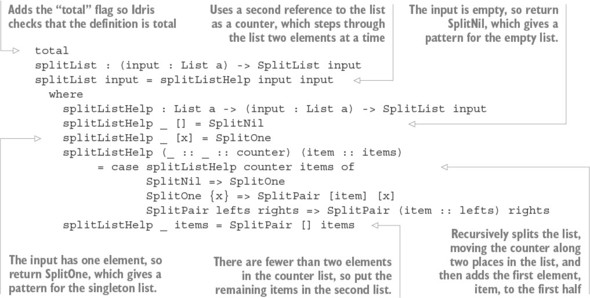

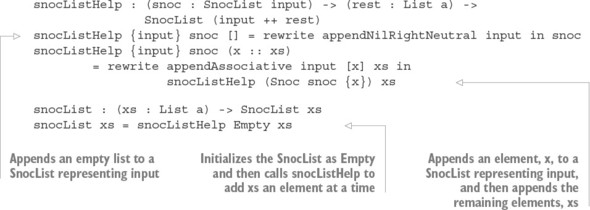

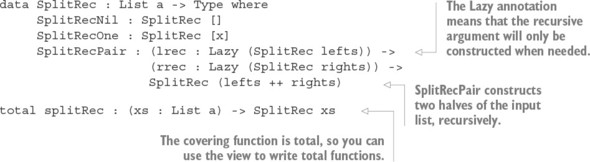

10.2. Recursive views: termination and efficiency

10.2.1. “Snoc” lists: traversing a list in reverse

10.2.2. Recursive views and the with construct

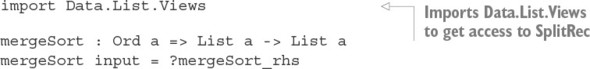

10.3. Data abstraction: hiding the structure of data using views

10.3.1. Digression: modules in Idris

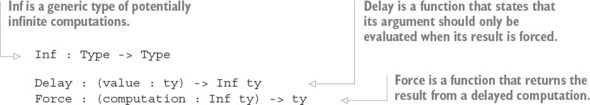

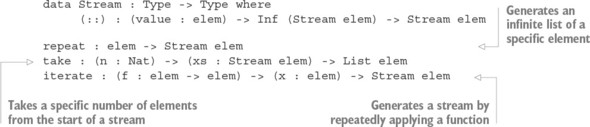

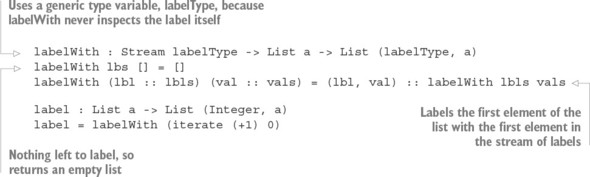

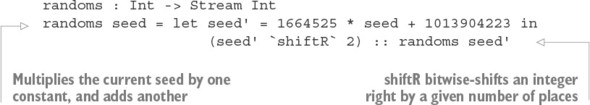

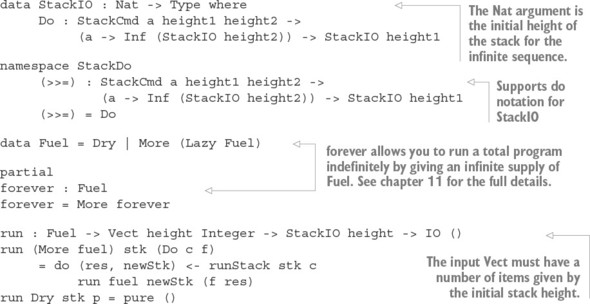

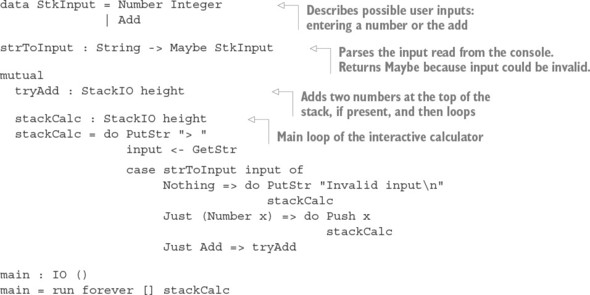

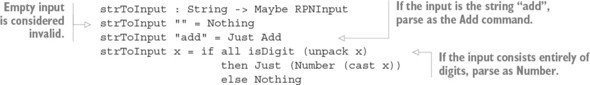

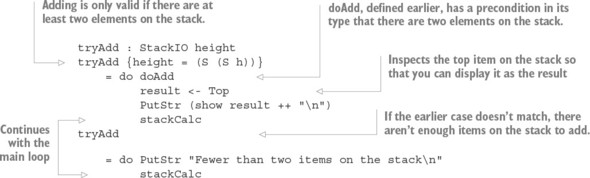

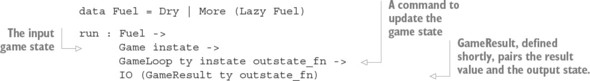

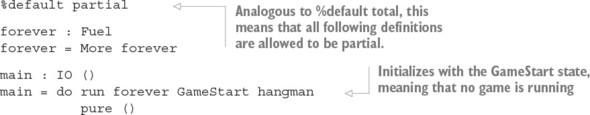

Chapter 11. Streams and processes: working with infinite data

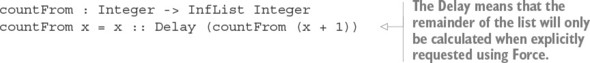

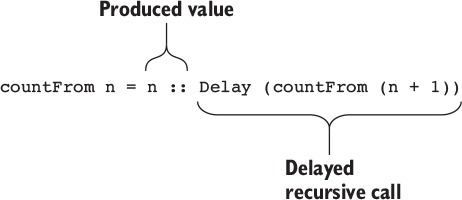

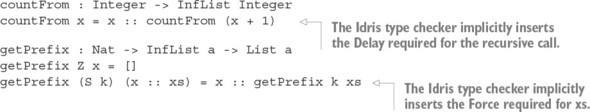

11.1. Streams: generating and processing infinite lists

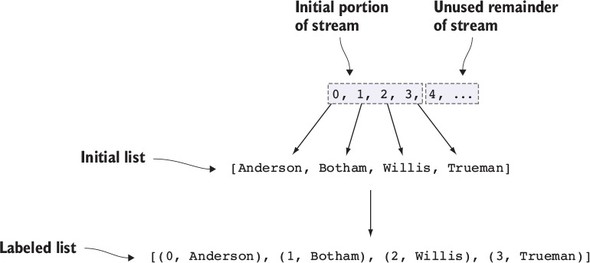

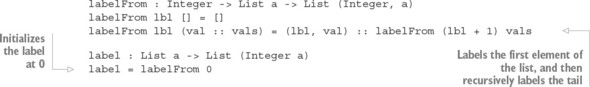

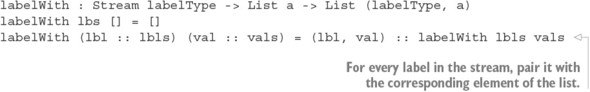

11.1.1. Labeling elements in a List

11.1.2. Producing an infinite list of numbers

11.1.3. Digression: what does it mean for a function to be total?

11.2. Infinite processes: writing interactive total programs

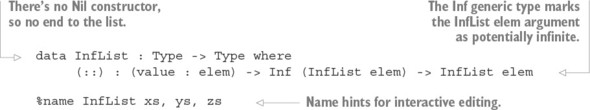

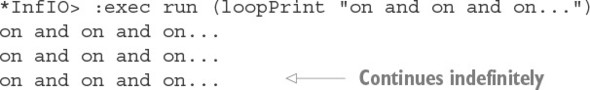

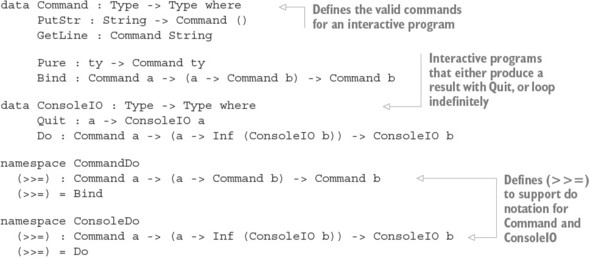

11.2.1. Describing infinite processes

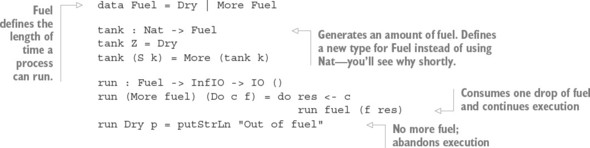

11.2.2. Executing infinite processes

11.2.3. Executing infinite processes as total functions

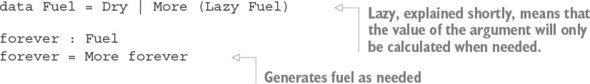

11.2.4. Generating infinite structures using Lazy types

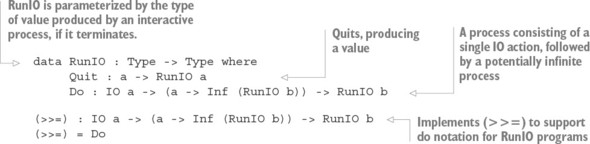

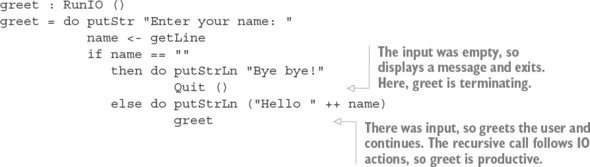

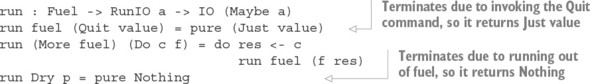

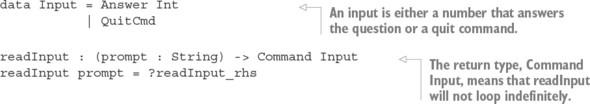

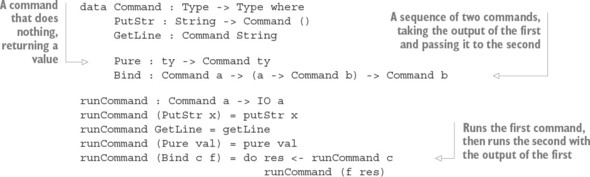

11.3. Interactive programs with termination

11.3.1. Refining InfIO: introducing termination

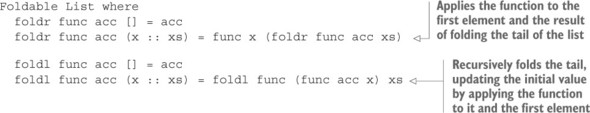

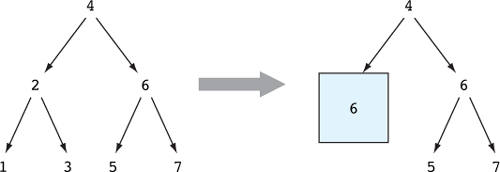

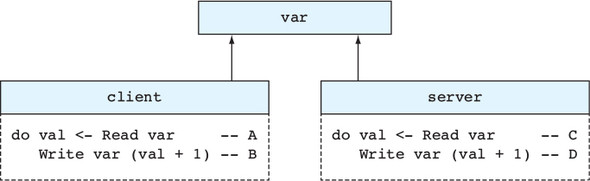

Chapter 12. Writing programs with state

12.1. Working with mutable state

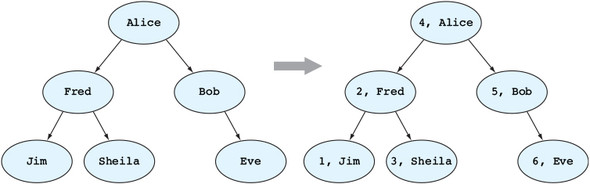

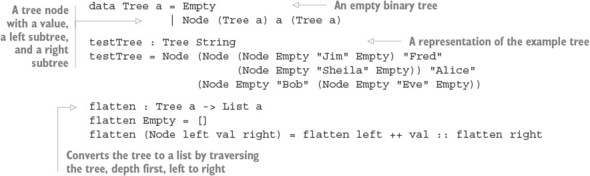

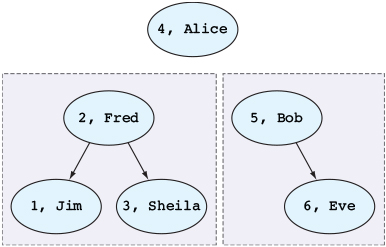

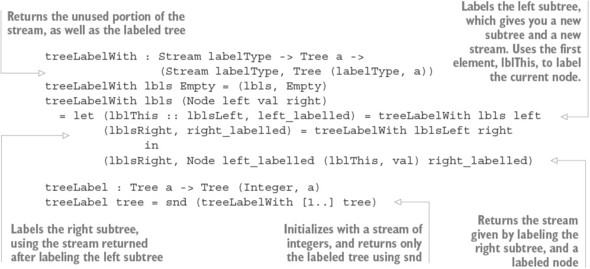

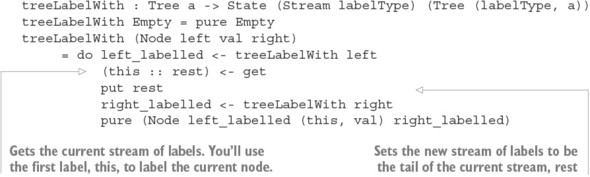

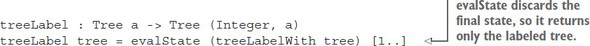

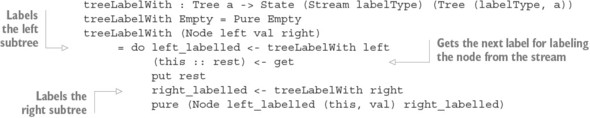

12.1.1. The tree-traversal example

12.1.2. Representing mutable state using a pair

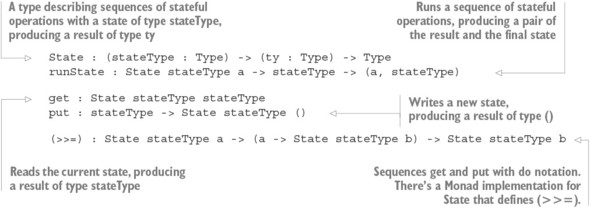

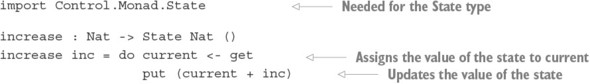

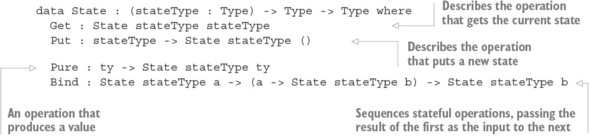

12.2. A custom implementation of State

12.2.1. Defining State and runState

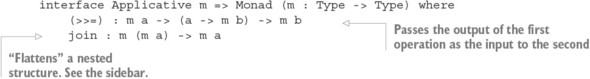

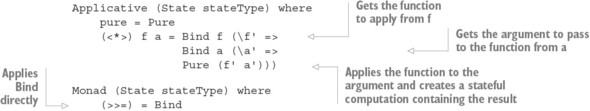

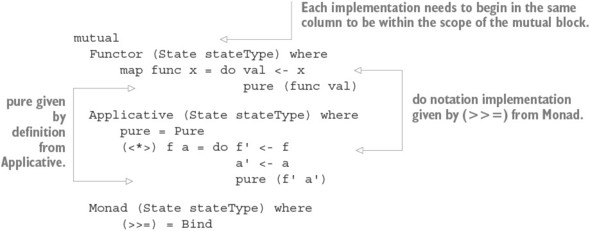

12.2.2. Defining Functor, Applicative, and Monad implementations for State

12.3. A complete program with state: working with records

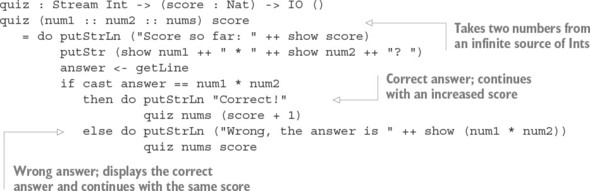

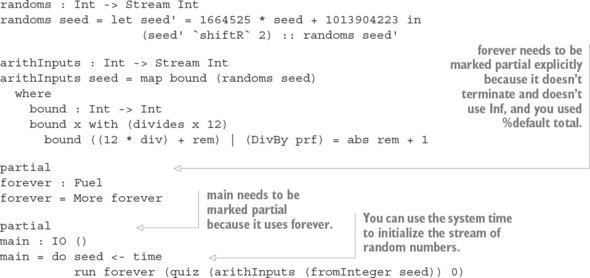

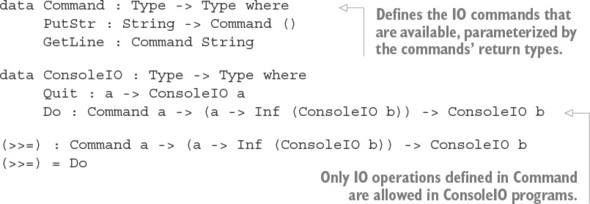

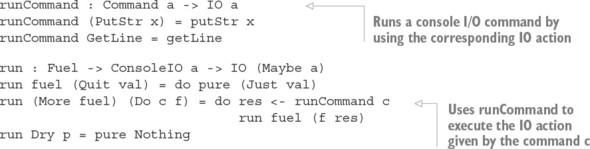

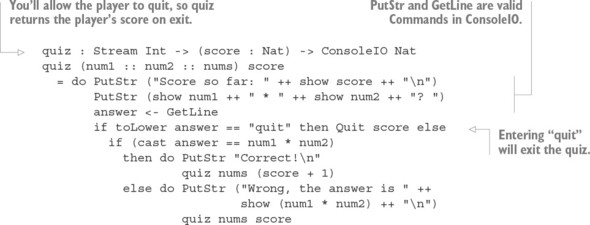

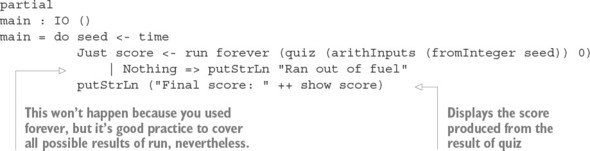

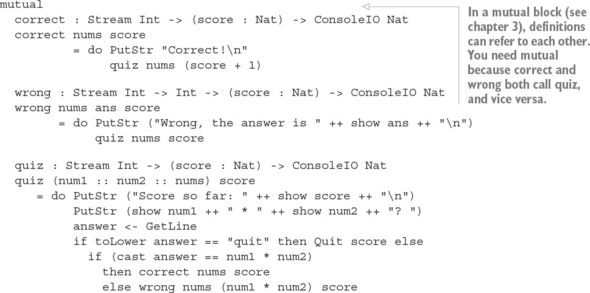

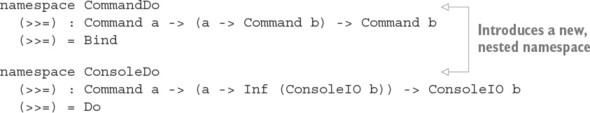

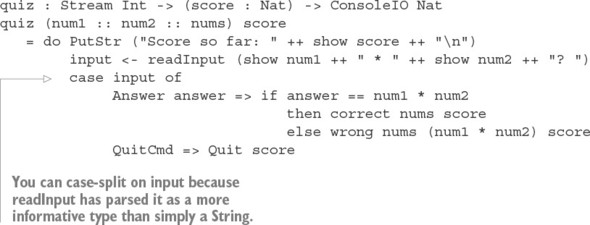

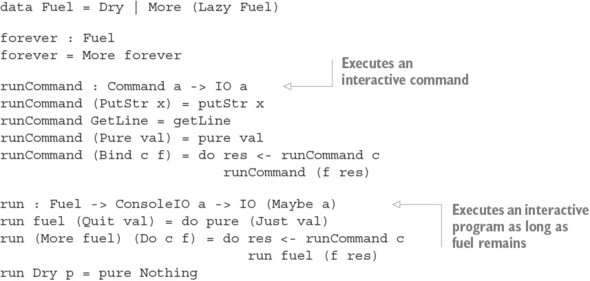

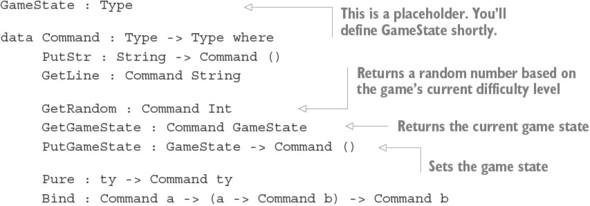

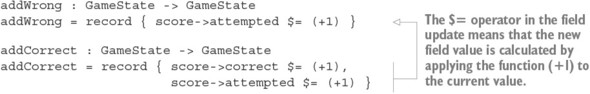

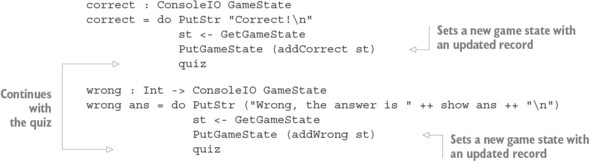

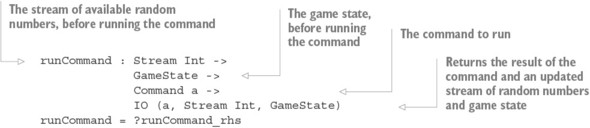

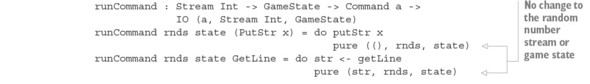

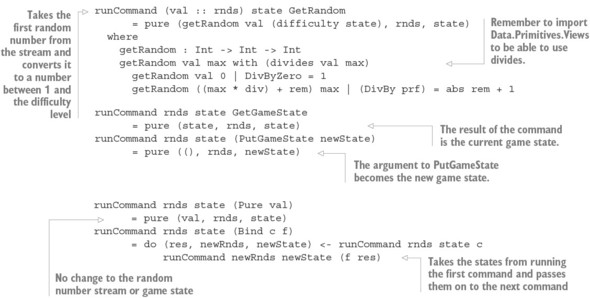

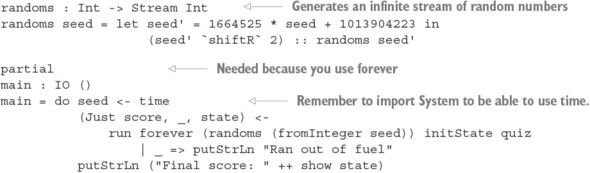

12.3.1. Interactive programs with state: the arithmetic quiz revisited

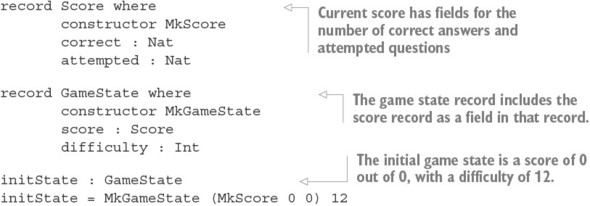

12.3.2. Complex state: defining nested records

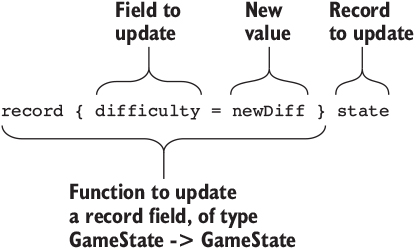

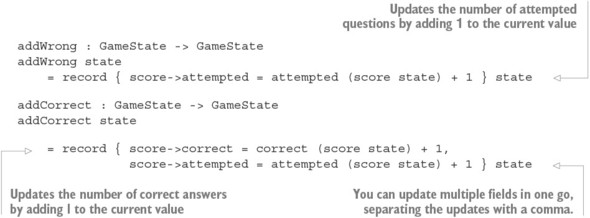

12.3.3. Updating record field values

12.3.4. Updating record fields by applying functions

12.3.6. Running interactive and stateful programs: executing the quiz

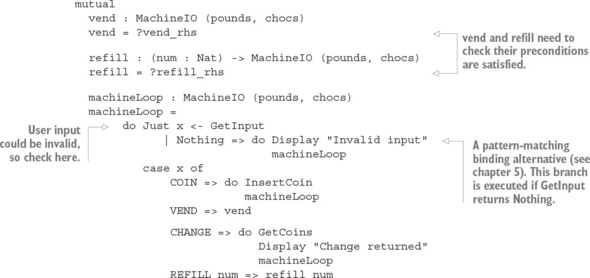

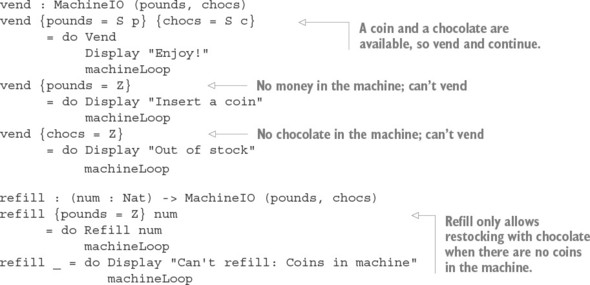

Chapter 13. State machines: verifying protocols in types

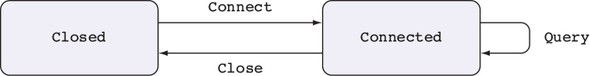

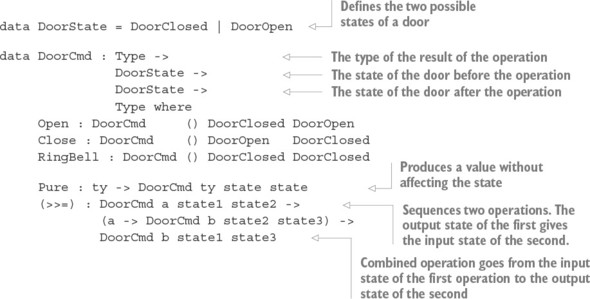

13.1. State machines: tracking state in types

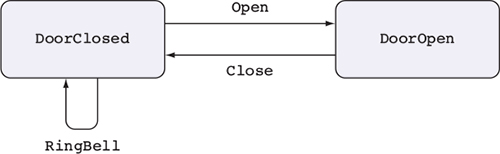

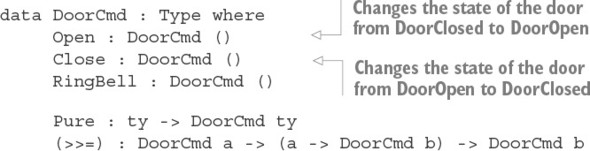

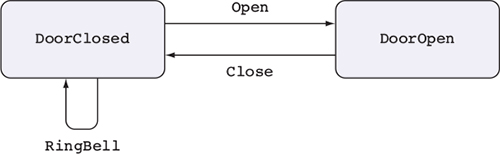

13.1.1. Finite state machines: modeling a door as a type

13.1.2. Interactive development of sequences of door operations

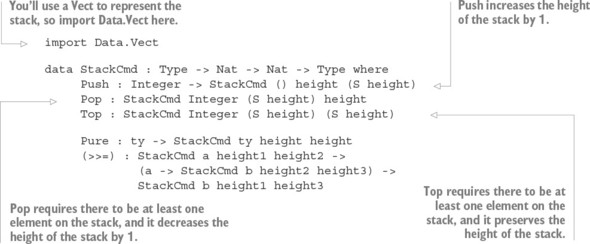

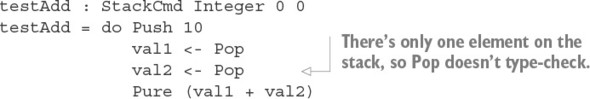

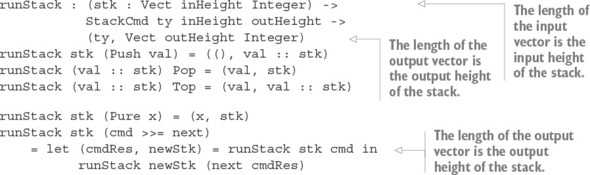

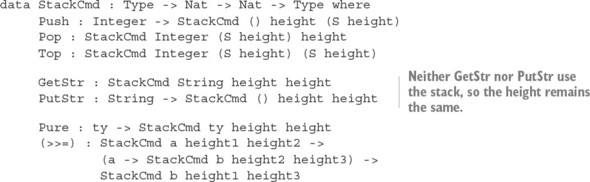

13.2. Dependent types in state: implementing a stack

13.2.1. Representing stack operations in a state machine

13.2.2. Implementing the stack using Vect

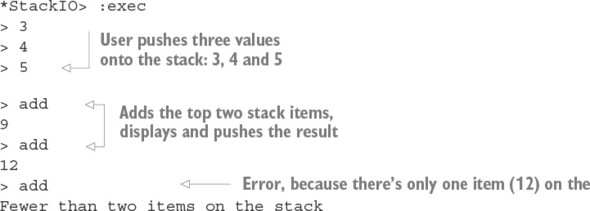

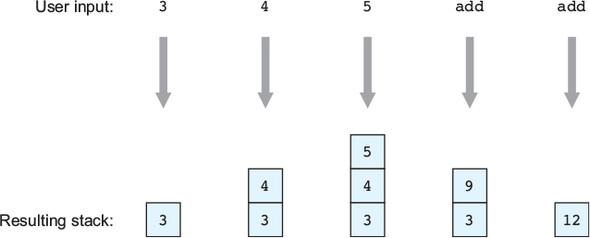

13.2.3. Using a stack interactively: a stack-based calculator

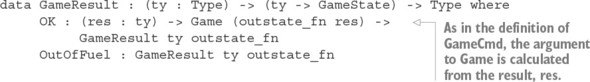

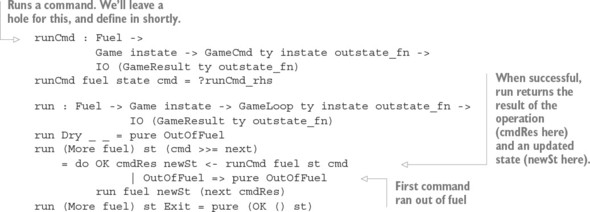

Chapter 14. Dependent state machines: handling feedback and errors

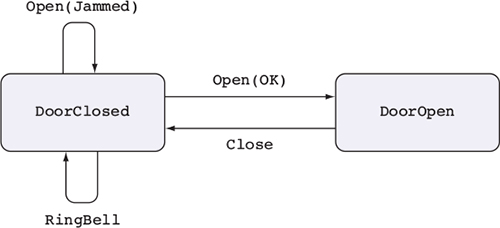

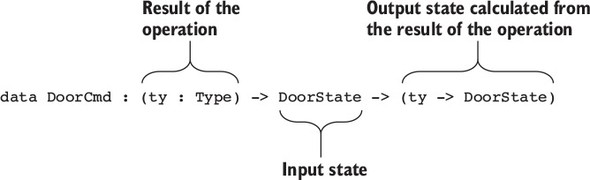

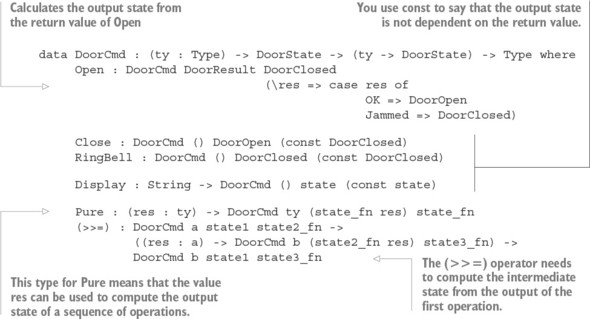

14.1. Dealing with errors in state transitions

14.1.1. Refining the door model: representing failure

14.1.2. A verified, error-checking, door-protocol description

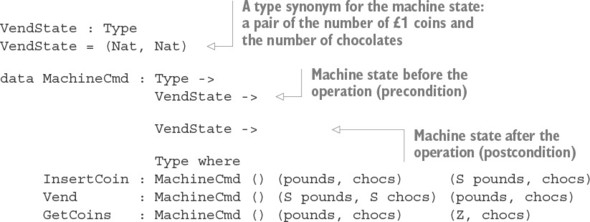

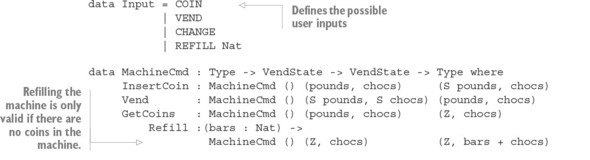

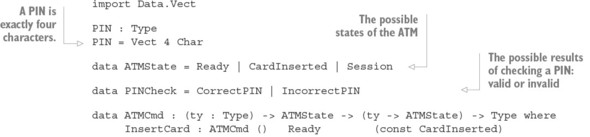

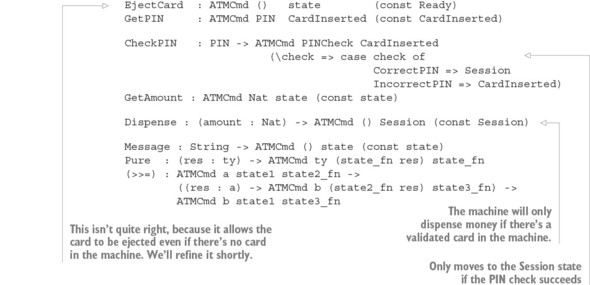

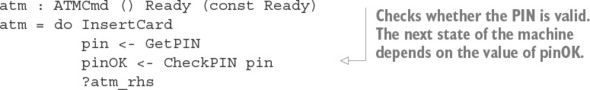

14.2. Security properties in types: modeling an ATM

14.2.1. Defining states for the ATM

14.2.2. Defining a type for the ATM

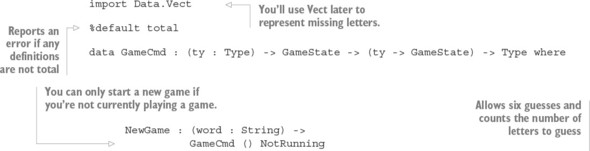

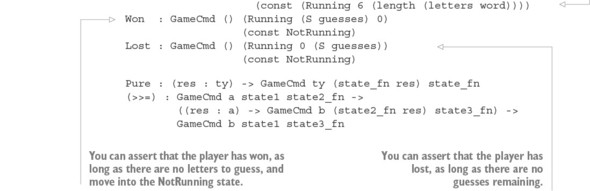

14.3. A verified guessing game: describing rules in types

14.3.1. Defining an abstract game state and operations

14.3.2. Defining a type for the game state

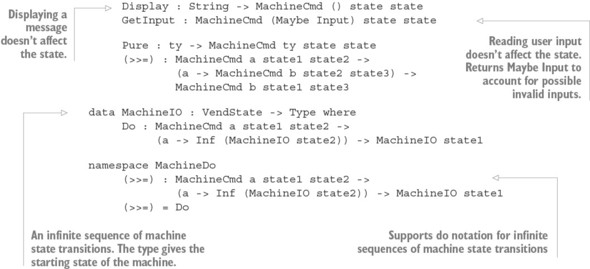

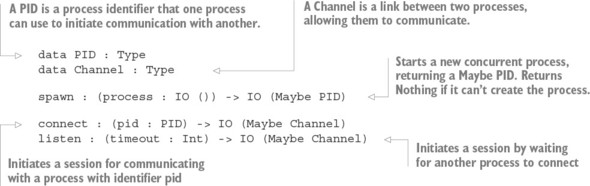

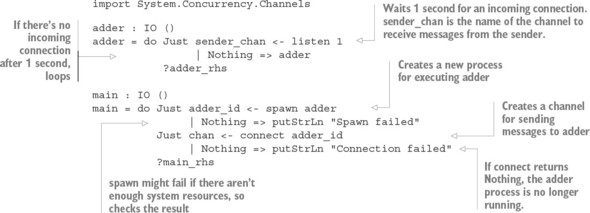

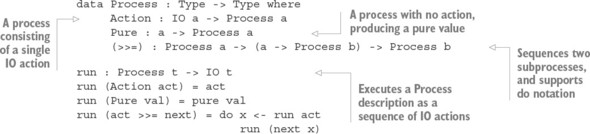

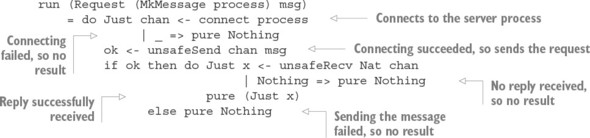

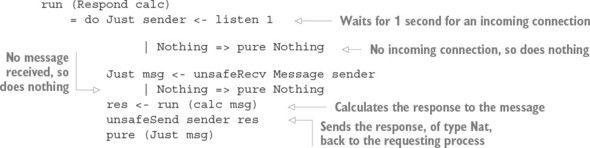

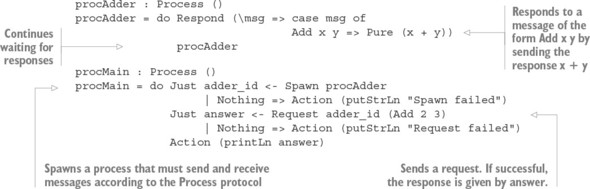

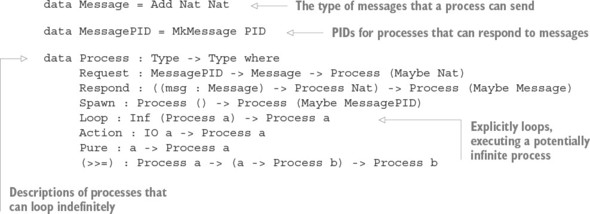

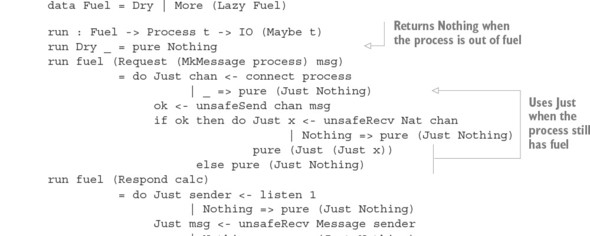

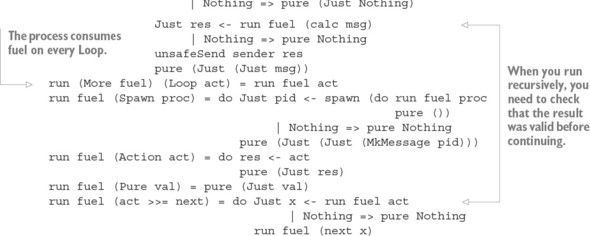

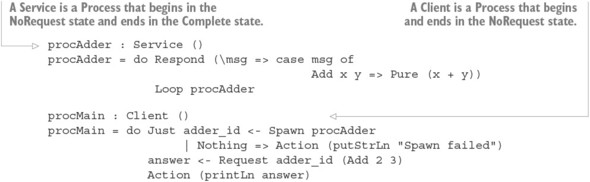

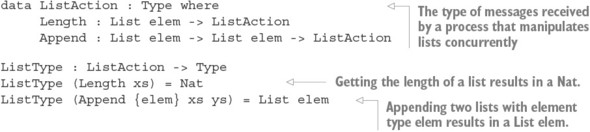

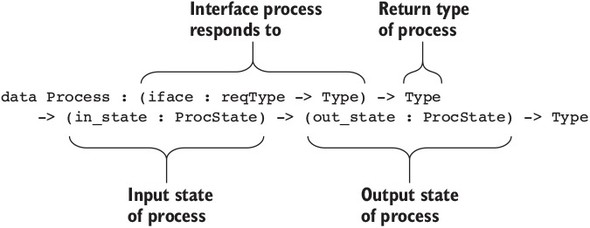

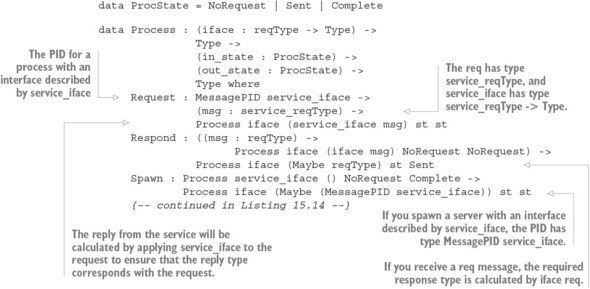

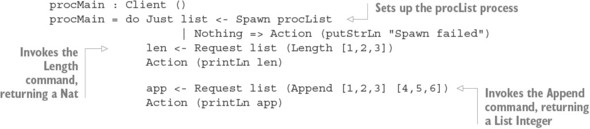

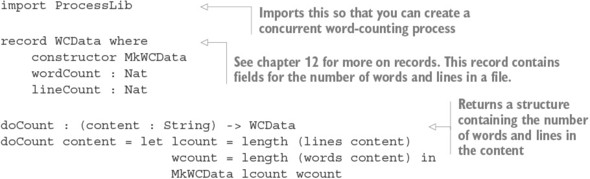

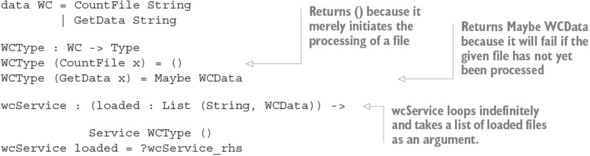

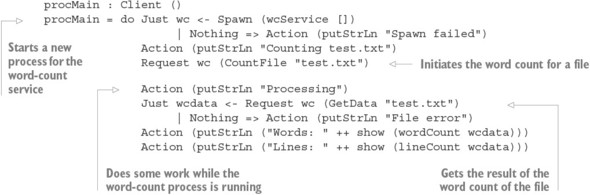

Chapter 15. Type-safe concurrent programming

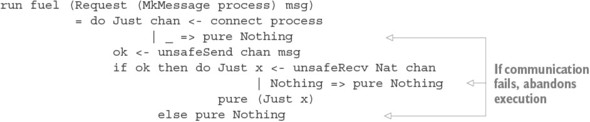

15.1. Primitives for concurrent programming in Idris

15.1.1. Defining concurrent processes

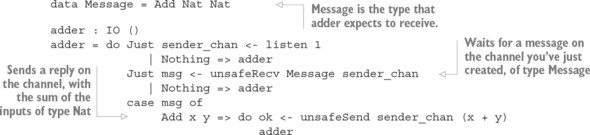

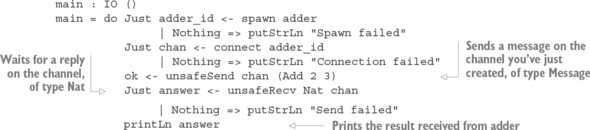

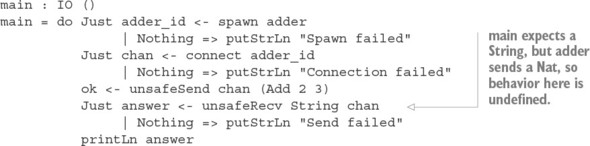

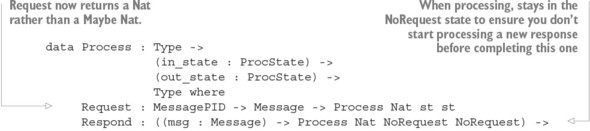

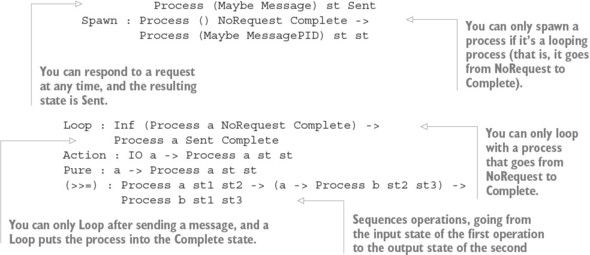

15.2. Defining a type for safe message passing

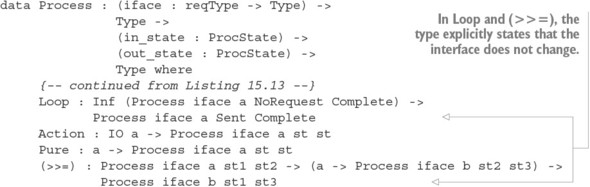

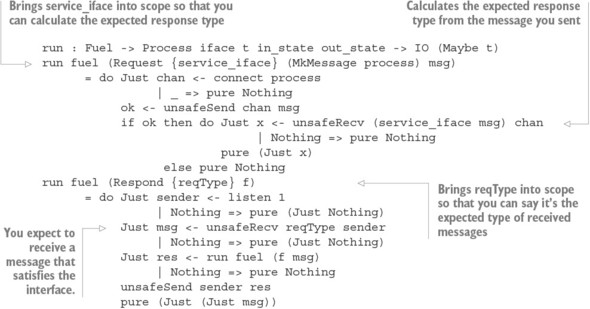

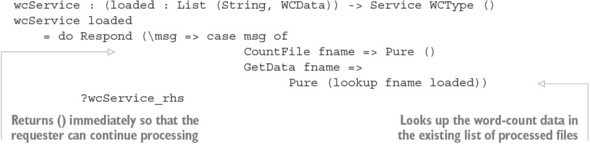

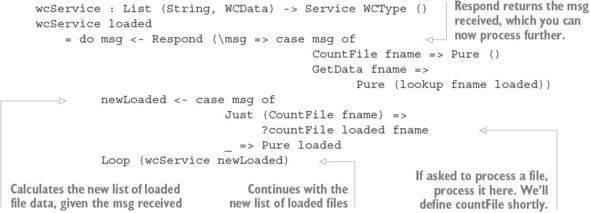

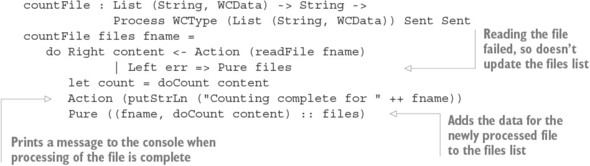

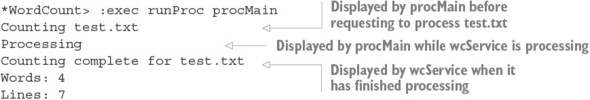

15.2.1. Describing message-passing processes in a type

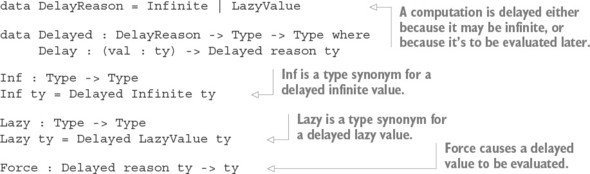

15.2.2. Making processes total using Inf

15.2.3. Guaranteeing responses using a state machine and Inf

15.2.4. Generic message-passing processes

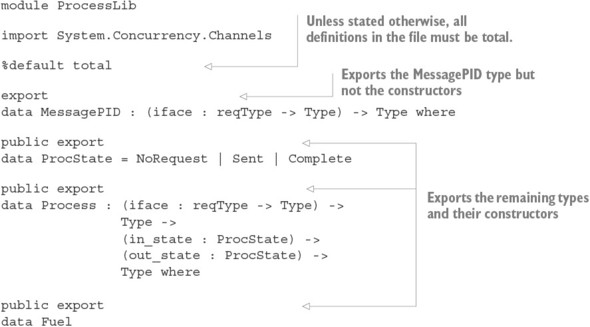

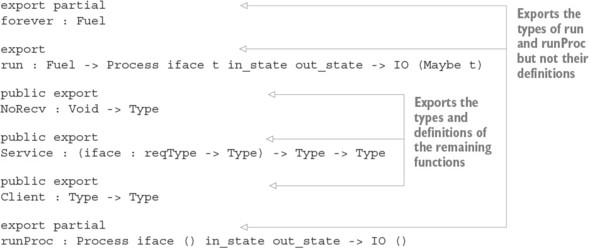

15.2.5. Defining a module for Process

Appendix A. Installing Idris and editor modes

The Idris compiler and environment

Appendix B. Interactive editing commands

Functional programming in Haskell

Preface

Computers are everywhere, and we rely on software daily. As well as running our desktop and laptop computers, software controls our communications, banking, transport infrastructure, and even our domestic appliances. Even so, it’s considered a fact of life that software is unreliable. If a laptop or mobile phone fails, it’s merely inconvenient and requires a restart (possibly accompanied by cursing over losing the last few minutes of work). If, on the other hand, the software controlling a business-critical application or server fails, significant time and money can be lost. For safety-critical systems, the repercussions could be even worse.

For many years, therefore, computer science researchers have been searching for ways to improve the robustness and safety of software. One approach among many is to use types to describe what a program is supposed to do. In particular, by using dependent types, you describe precise properties of a program. The idea is that if you can express a program’s intention in its type, and the program successfully type-checks, then the program must behave as intended. An important (if ambitious and long-term) goal of the Idris programming language is to make the results of this research accessible to software developers in general, and correspondingly reduce the possibility of critical software failures.

Initially, this book’s focus was programming in Idris: showing how to use its type system to guarantee important properties of programs. Under the guidance of development editor Dan Maharry, and thanks to the efforts of technical development editor Andrew Gibson, it has evolved to become as much about the process of programming with dependent types as about how the resulting programs work. You’ll learn about the fundamentals of dependent types, how to use types to define programs interactively, and how to refine programs and types as your understanding of a problem evolves. You’ll also learn about some real-world applications of type-driven development, particularly in dealing with state, protocols, and concurrency.

Idris itself arose as a result of my own research into program verification and language design with dependent types. After spending several years immersed in the concept of programming with dependent types, I felt there was a need for a language designed for developers as well as researchers. I hope that you have as much fun learning about type-driven development with Idris as I have had developing it!

Acknowledgments

Many people have helped in the writing of this book, and it wouldn’t exist without them. In particular, I thank Dan Maharry, who encouraged me to reveal the ideas of type-driven development much more clearly. The mantra of “type, define, refine,” which appears throughout the book, was Dan’s suggestion. I also owe many thanks to Andrew Gibson, who has meticulously worked through all the examples and exercises throughout the book, making sure they work, checking that the exercises are solvable, and suggesting many improvements to the text and explanations. Overall, I’d like to thank the team at Manning Publications for helping to make this book a reality.

The design of Idris owes much to several decades of research into type theory, functional programming, and language design. I’m grateful to James McKinna and Conor McBride in particular for teaching me the fundamentals of type theory when I was a graduate student at Durham University, and for their continued advice and encouragement since. I’d also like to thank the researchers and developers responsible for the languages and systems that have inspired my work, namely, tools such as Haskell, Epigram, Agda, and Coq. Idris couldn’t exist without the work that has come before, and I can only hope that it, in turn, inspires others in the future. See appendix D for some references to the work that inspired Idris.

Several colleagues and students at the University of St. Andrews and elsewhere have provided useful feedback on earlier drafts of chapters and have been patient while I worked on the book instead of working on other things. In particular, I would like to thank Ozgur Akgun, Nicola Botta, Sam Elliot, Simon Fowler, Nicolas Gagliani (who contributed the extension to the Atom editor that you’ll use throughout the book), Jan de Muijnck-Hughes, Markus Pfeiffer, Chris Schwaab, and Matúš Tejiščák for their comments and suggestions. My sincere apologies to anyone else I’ve forgotten to name!

Readers who have purchased early access and reviewers of earlier drafts have contributed many useful comments and suggestions. Those reviewers include Alexander A. Myltsev, Álvaro Falquina, Arnaud Bailly, Carsten Jørgensen, Christine Koppelt, Giovanni Ruggiero, Ian Dees, Juan Gabriel Bono, Mattias Lundell, Phil de Joux, Rintcius Blok, Satadru Roy, Sergey Selyugin, Todd Fine, and Vitaly Bragilevsky.

I couldn’t have implemented Idris on my own. Since I began developing the current version in late 2011, there have been many contributors, but most of all I would like to thank David Christiansen, who is responsible for much of the polish in the Idris REPL and the interactive editing tools; he has also worked hard to help newcomers to the project. Thanks are also due to the other contributors: Ozgur Akgun, Ahmad Salim Al-Sibahi, Edward Chadwick Amsden, Michael R. Bernstein, Jan Bessai, Nicola Botta, Vitaly Bragilevsky, Jakob Brünker, Alyssa Carter, Carter Charbonneau, Aaron Craelius, Jason Dagit, Adam Sandberg Eriksson, Guglielmo Fachini, Simon Fowler, Zack Grannan, Sean Hunt, Cezar Ionescu, Heath Johns, Irene Knapp, Paul Koerbitz, Niklas Larsson, Shea Levy, Mathnerd314, Hannes Mehnert, Mekeor Melire, Melissa Mozifian, Jan de Muijnck-Hughes, Dominic Mulligan, Echo Nolan, Tom Prince, raichoo, Philip Rasmussen, Aistis Raulinaitis, Reynir Reynisson, Seo Sanghyeon, Benjamin Saunders, Alexander Shabalin, Jeremy W. Sherman, Timo Petteri Sinnemäki, JP Smith, startling, Chetan T, Matúš Tejiščák, Dirk Ullrich, Leif Warner, Daniel Waterworth, Eric Weinstein, Jonas Westerlund, Björn Aili, and Zheng Jihui.

Finally, thanks go to my parents, whose purchase of a BBC Micro in 1983 set me off on this path; and to Emma, for waiting so patiently for me to finish this, and for bringing me coffee to keep me going.

About this Book

Type-Driven Development with Idris is about making types work for you. Types are often seen as a tool for checking for errors, with the programmer writing a complete program first and using the type checker to detect errors. In type-driven development, you use types as a tool for constructing programs, and the type checker as your assistant to guide you to a complete and working program.

This book begins by describing what you can express with types; then, it introduces the core features of the Idris programming language. Finally, it describes some more-practical applications of type-driven development.

Who should read this book

This book is aimed at developers who want to learn about the state of the art in using sophisticated type systems to help develop robust software. It aims to provide an accessible introduction to dependent types, and to show how modern type-based techniques can be applied to real-world problems.

Readers will ideally already be familiar with functional programming concepts such as closures and higher-order functions, although the book introduces these and other concepts as necessary. Knowledge of another functional programming language such as Haskell, OCaml, or Scala will be particularly helpful, though none is assumed.

Roadmap

This book is divided into three parts. Part 1 (chapters 1 and 2) introduces the concepts and gives a tour of the Idris programming language:

- Chapter 1 introduces type-driven development and gets you started with the Idris environment.

- Chapter 2 covers the basics of Idris programming, including primitive types and structuring Idris programs.

Part 2 (chapters 3–10) introduces the core language features of Idris:

- Chapter 3 discusses interactive development using the Atom editor and describes how using more-precise types means that the type checker can help you write programs.

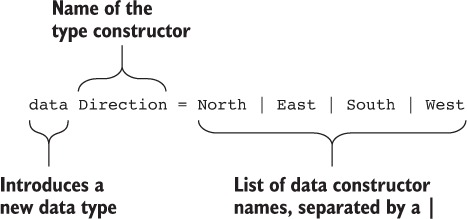

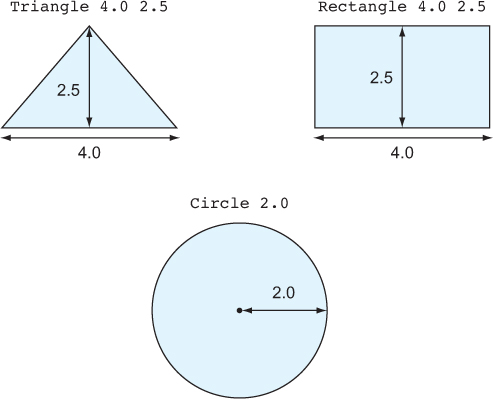

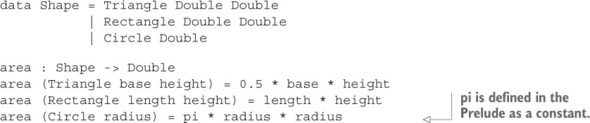

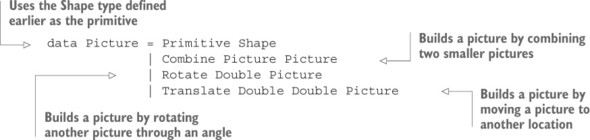

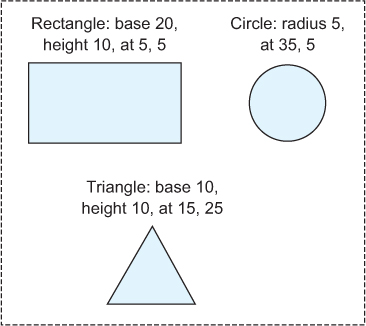

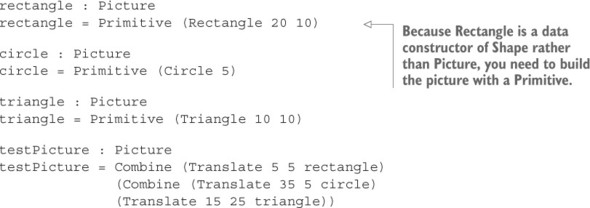

- Chapter 4 explains how to define your own data types and presents a first example of writing a larger interactive program in the type-driven style.

- Chapter 5 describes interactive programs in more depth, including how to use types to help validate user inputs to interactive programs.

- Chapter 6 introduces type-level programming, showing how to write functions that calculate types and how to use them in practice.

- Chapter 7 describes how to use interfaces to write programs with generic types.

- Chapter 8 explains how you can use types to express relationships between data, particularly to describe properties of data and to guarantee that functions behave a certain way.

- Chapter 9 explains further how types can express contracts that functions must satisfy, including an example that shows how to use types to describe the state of a system.

- Chapter 10 introduces views, which are alternative ways of inspecting and traversing data structures.

Part 3 (chapters 11–15) describes some applications of Idris to real-world software development, particularly working with state and interactive programs:

- Chapter 11 describes how to work with potentially infinite data, such as streams, and how to write and reason about interactive programs that could run indefinitely.

- Chapter 12 explains how to write programs with state and how to represent and manipulate complex state using records.

- Chapter 13 shows how to express a state machine in an Idris type, and how to use the type to guarantee that programs follow protocols correctly.

- Chapter 14 describes more-sophisticated state machines, how to handle errors and feedback from an environment, and how to represent security properties of a system in its type.

- Chapter 15 concludes the book with a worked example: type-driven development of a small library for concurrent programming.

In general, each chapter builds on concepts introduced in earlier chapters, so it’s intended that you read the chapters in order. Most importantly, the book describes the process of type-driven development and constructing programs interactively from a type. Therefore, I strongly recommend working through the examples on a computer as you read. Furthermore, if you’re reading the eBook, type in the examples—don’t just copy and paste.

There are exercises throughout each chapter, so, as you read, make sure that you complete the exercises to reinforce your understanding. Sample solutions are available online from the book’s website at www.manning.com/books/type-driven-development-with-idris.

There are four appendices: Appendix A describes how to install Idris and the Atom editor mode, which we’ll use throughout the book. Appendix B summarizes the interactive editing commands supported by Atom. Appendix C summarizes the commands you can use in the Idris environment. Finally, appendix D gives references to some of the work that inspired Idris, and where you can learn more about the theoretical background and related tools.

Code conventions and downloads

This book contains many examples of source code both in numbered listings and inline with normal text. In both cases, source code is formatted in a fixed-width font like this to separate it from ordinary text.

In many cases, the original source code has been reformatted; I’ve added line breaks and reworked indentation to accommodate the available page space in the book. Additionally, comments in the source code have often been removed from the listings when the code is described in the text. Code annotations accompany many of the listings, highlighting important concepts.

All of the code in this book is available online from the book’s website (www.manning.com/books/type-driven-development-with-idris) and has been tested with Idris 1.0. The code is also available in a Git repository here: https://github.com/edwinb/TypeDD-Samples.

Author Online

Purchase of Type-Driven Development with Idris includes free access to a private web forum run by Manning Publications where you can make comments about the book, ask technical questions, and receive help from the author and from other users. To access the forum and subscribe to it, point your web browser to www.manning.com/books/type-driven-development-with-idris. This page provides information on how to get on the forum once you’re registered, what kind of help is available, and the rules of conduct on the forum.

Manning’s commitment to our readers is to provide a venue where a meaningful dialog between individual readers and between readers and the author can take place. It’s not a commitment to any specific amount of participation on the part of the author, whose contribution to the forum remains voluntary (and unpaid). We suggest you try asking him challenging questions lest his interest stray!

The Author Online forum and the archives of previous discussions will be accessible from the publisher’s website as long as the book is in print.

Other online resources

If you’d like to learn more about Idris, you can find more resources on the Idris website: http://idris-lang.org/. You can also find help in several other places:

- The idris-lang Google Group is an active group discussing all aspects of Idris. The group welcomes questions from beginners and more-advanced users alike.

- There is an IRC channel, #idris on irc.freenode.net, which is similarly open to questions.

- You can ask and answer questions using the Idris tag on Stack Overflow.

About the Author

EDWIN BRADY leads the design and implementation of the Idris programming language. He is a lecturer in Computer Science at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, and he regularly speaks at conferences. When he’s not doing that, you might find him playing a game of Go, watching a game of cricket, or somewhere up a hill in the middle of Scotland.

About the Cover Illustration

The figure on the cover of Type-Driven Development with Idris is captioned “La Gasconne,” or “A woman from Gascony.” The illustration is taken from a collection of works by many artists, edited by Louis Curmer and published in Paris in 1841. The title of the collection is Les Français peints par eux-mêmes, which translates as The French People Painted by Themselves. Each illustration is finely drawn and colored by hand, and the rich variety of drawings in the collection reminds us vividly of how culturally apart the world’s regions, towns, villages, and neighborhoods were just 200 years ago. Isolated from each other, people spoke different dialects and languages. In the streets or in the countryside, it was easy to identify where they lived and what their trade or station in life was just by their dress.

Dress codes have changed since then, and the diversity by region, so rich at the time, has faded away. It’s now hard to tell apart the inhabitants of different continents, let alone different towns or regions. Perhaps we have traded cultural diversity for a more varied personal life—certainly for a more varied and fast-paced technological life.

At a time when it’s hard to tell one computer book from another, Manning celebrates the inventiveness and initiative of the computer business with book covers based on the rich diversity of regional life of two centuries ago, brought back to life by pictures from collections such as this one.

Part 1. Introduction

In this first part, you’ll get started with Idris and learn about the ideas behind type-driven development. I’ll take you on a brief tour of the Idris environment, and you’ll write some simple but complete programs.

In the first chapter, I’ll explain more about what I mean by type-driven development. Most importantly, I’ll define what I mean by “type” and give several examples of how you can use expressive types to describe the intended purpose of your programs more precisely. I’ll also introduce the two most distinctive features of the Idris language: holes, which stand for parts of programs that are yet to be written, and the use of types as a first-class language construct.

Before you get too deeply into type-driven development in Idris, it’s important to have a solid grasp of the fundamentals of the language. Therefore, in chapter 2, I’ll discuss some of the primitive language constructs, many of which will be familiar to you from other languages, and show how to construct complete programs in Idris.

Chapter 1. Overview

This chapter covers

- Introducing type-driven development

- The essence of pure functional programming

- First steps with Idris

This book teaches a new approach to building robust software, type-driven development, using the Idris programming language. Traditionally, types are seen as a tool for checking for errors, with the programmer writing a complete program first and using either the compiler or the runtime system to detect type errors. In type-driven development, we use types as a tool for constructing programs. We put the type first, treating it as a plan for a program, and use the compiler and type checker as our assistant, guiding us to a complete and working program that satisfies the type. The more expressive the type is that we give up front, the more confidence we can have that the resulting program will be correct.

Types and tests

The name “type-driven development” suggests an analogy to test-driven development. There’s a similarity, in that writing tests first helps establish a program’s purpose and whether it satisfies some basic requirements. The difference is that, unlike tests, which can usually only be used to show the presence of errors, types (used appropriately) can show the absence of errors. But although types reduce the need for tests, they rarely eliminate it entirely.

In Idris, types are a first-class language construct. Types can be manipulated, used, passed as arguments to functions, and returned from functions just like any other value, such as numbers, strings, or lists. This is a simple but powerful idea:

- It allows relationships to be expressed between values; for example, that two lists have the same length.

- It allows assumptions to be made explicit and checkable by the compiler. For example, if you assume that a list is non-empty, Idris can ensure this assumption always holds before the program is run.

- If desired, it allows program behavior to be formally stated and proven correct.

In this chapter, I’ll introduce the Idris programming language and give a brief tour of its features and environment. I’ll also provide an overview of type-driven development, discussing why types matter in programming languages and how they can be used to guide software development. But first, it’s important to understand exactly what we mean when we talk about “types.”

1.1. What is a type?

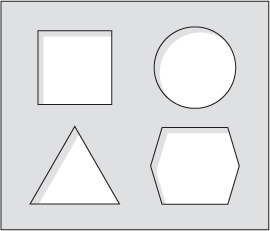

We’re taught from an early age to recognize and distinguish types of objects. As a young child, you may have had a shape-sorter toy. This consists of a box with variously shaped holes in the top (see figure 1.1) and some shapes that fit through the holes. Sometimes they’re equipped with a small plastic hammer. The idea is to fit each shape (think of this as a “value”) into the appropriate hole (think of this as a “type”), possibly with coercion from the hammer.

Figure 1.1. The top of a shape-sorter toy. The shapes correspond to the types of objects that will fit through the holes.

In programming, types are a means of classifying values. For example, the values 94, "thing", and [1,2,3,4,5] could respectively be classified as an integer, a string, and a list of integers. Just as you can’t put a square shape in a round hole in the shape sorter, you can’t use a string like "thing" in a part of a program where you need an integer.

All modern programming languages classify values by type, although they differ enormously in when and how they do so (for example, whether they’re checked statically at compile time or dynamically at runtime, whether conversions between types are automatic or not, and so on).

Types serve several important roles:- For a machine, types describe how bit patterns in memory are to be interpreted.

- For a compiler or interpreter, types help ensure that bit patterns are interpreted consistently when a program runs.

- For a programmer, types help name and organize concepts, aiding documentation and supporting interactive editing environments.

From our point of view in this book, the most important purpose of types is the third. Types help programmers in several ways:

- By allowing for the naming and organization of concepts (such as Square, Circle, Triangle, and Hexagon)

- By providing explicit documentation of the purposes of variables, functions, and programs

- By driving code completion in an interactive editing environment

As you’ll see, type-driven development makes extensive use of code completion in particular. Although all modern, statically typed languages support code completion to some extent, the expressivity of the Idris type system leads to powerful automatic code generation.

1.2. Introducing type-driven development

Type-driven development is a style of programming in which we write types first and use those types to guide the definition of functions. The overall process is to write the necessary data types, and then, for each function, do the following:

- Write the input and output types.

- Define the function, using the structure of the input types to guide the implementation.

- Refine and edit the type and function definition as necessary.

When you write a program, you’ll often have a conceptual model in your head (or, if you’re disciplined, even on paper) of how it’s supposed to work, how the components interact, and how the data is organized. This model is likely to be quite vague at first and will become more precise as the program evolves and your understanding of the concept develops.

Types allow you to make these models explicit in code and ensure that your implementation of a program matches the model in your head. Idris has an expressive type system that allows you to describe a model as precisely as you need, and to refine the model at the same time as developing the implementation.

In type-driven development, instead of thinking of types in terms of checking, with the type checker criticizing you when you make a mistake, you can think of types as being a plan, with the type checker acting as your guide, leading you to a working, robust program. Starting with a type and an empty function body, you gradually add details to the definition until it’s complete, regularly using the

compiler to check that the program so far satisfies the type. Idris, as you’ll soon see, strongly encourages this style of programming by allowing incomplete function definitions to be checked, and by providing an expressive language for describing types.To illustrate further, in this section I’ll show some examples of how you can use types to describe in detail what a program is intended to do: matrix arithmetic, modeling an automated teller machine (ATM), and writing concurrent programs. Then, I’ll summarize the process of type-driven development and introduce the concept of dependent types, which will allow you to express detailed properties of your programs.

1.2.1. Matrix arithmetic

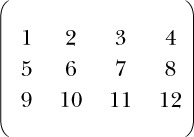

A matrix is a rectangular grid of numbers, arranged in rows and columns. They have several scientific applications, and in programming they have applications in cryptography, 3D graphics, machine learning, and data analytics. The following, for example, is a 3 × 4 matrix:

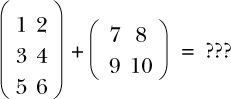

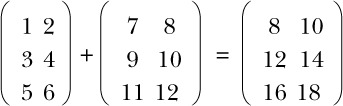

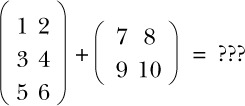

You can implement various arithmetic operations on matrices, such as addition and multiplication. To add two matrices, you add the corresponding elements, as you see here:

When programming with matrices, if you begin by defining a Matrix data type, then addition requires two inputs of type Matrix and gives an output of type Matrix. But because adding matrices involves adding corresponding elements of the inputs, what happens if the two inputs have different dimensions, as here?

It’s likely that if you’re trying to add matrices of different dimensions, then you’ve made a mistake somewhere. So, instead of using a Matrix type, you could refine the

type so that it includes the dimensions of the matrix, and require that the two input matrices have the same dimensions:- The first example of a 3 × 4 matrix now has type Matrix 3 4.

- The first (correct) example of addition takes two inputs of type Matrix 3 2 and gives an output of type Matrix 3 2.

By including the dimensions in the type of a matrix, you can describe the input and output types of addition in such a way that it’s a type error to try to add matrices of different sizes. If you try to add a Matrix 3 2 and a Matrix 2 2, your program won’t compile, let alone run.

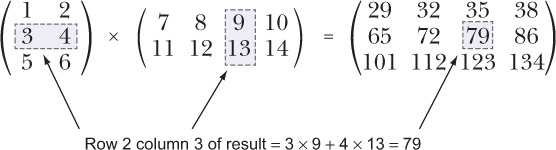

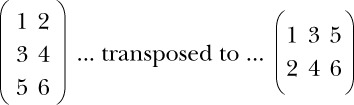

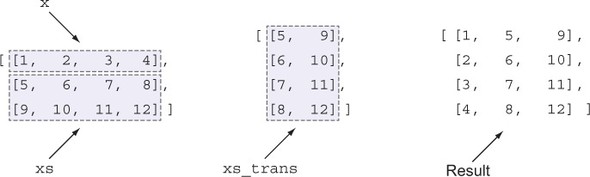

If you include the dimensions of a matrix in its type, then you need to think about the relationship between the dimensions of the input and output for every matrix operation. For example, transposing a matrix involves switching the rows to columns and vice versa, so if you transpose a 3 × 2 matrix, you’ll end up with a 2 × 3 matrix:

The input type of this transposition is Matrix 3 2, and the output type is Matrix 2 3.

In general, rather than giving exact dimensions in the type, we’ll use variables to describe the relationship between the dimensions of the inputs and the dimensions of the outputs. Table 1.1 shows the relationships between the dimensions of inputs and outputs for three matrix operations: addition, multiplication, and transposition.

Table 1.1. Input and output types for matrix operations. The names x, y, and z describe, in general, how the dimensions of the inputs and outputs are related.

| Operation | Input types | Output type |

|---|---|---|

| Add | Matrix x y, Matrix x y | Matrix x y |

| Multiply | Matrix x y, Matrix y z | Matrix x z |

| Transpose | Matrix x y | Matrix y x |

We’ll look at matrices in depth in chapter 3, where we’ll work through an implementation of matrix transposition in detail.

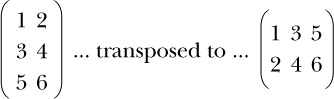

1.2.2. An automated teller machine

As well as using types to describe the relationships between the inputs and outputs of functions, as with matrix operations, you can describe precisely when operations are valid. For example, if you’re implementing software to drive an ATM, you’ll want to guarantee that the machine will dispense cash only after a user has entered a card and validated their personal identification number (PIN).

To see how this works, we’ll need to consider the possible states that an ATM can be in:

- Ready—The ATM is ready and waiting for a user to insert a card.

- CardInserted—The ATM is waiting for a user, having inserted a card, to enter their PIN.

- Session—A validated session is in progress, with the ATM, having validated the user’s PIN, ready to dispense cash.

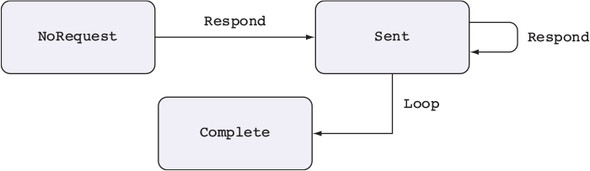

An ATM supports several basic operations, each of which is valid only when the machine is in a specific state, and each of which might change the state of the machine, as illustrated in figure 1.2. These are the basic operations:

- InsertCard—Waits for the user to insert a card

- EjectCard—Ejects a card from the machine

- GetPIN—Prompts the user to enter a PIN

- CheckPIN—Checks whether an entered PIN is correct

- Dispense—Dispenses cash

Figure 1.2. The states and valid operations on an ATM. Each operation is valid only in specific states and can change the state of the machine. CheckPIN changes the state only if the entered PIN is correct.

Whether an operation is valid or not depends on the state of the machine. For example, InsertCard is valid only in the Ready state, because that’s the only state where there’s no card already in the machine. Also, Dispense is valid only in the Session state, because that’s the only state where there’s a validated card in the machine.

Furthermore, executing one of these operations can change the state of the machine. For example, InsertCard changes the state from Ready to CardInserted, and CheckPIN changes the state from CardInserted to Session, provided that the entered PIN is correct.

State machines and types

Figure 1.2 illustrates a state machine, describing how operations affect the overall state of a system. State machines are often present, implicitly, in real-world systems. For example, when you open, read,

and then close a file, you change the state of the file with the open and close operations. As you’ll see in chapter 13, types allow you to make these state changes explicit, guarantee that you’ll execute operations only when they’re valid, and help you use resources correctly.By defining precise types for each of the operations on the ATM, you can guarantee, by type checking, that the ATM will execute only valid operations. If, for example, you try to implement a program that dispenses cash without validating a PIN, the program won’t compile. By defining valid state transitions explicitly in types, you get strong and machine-checkable guarantees about the correctness of their implementation. We’ll look at state machines in chapter 13, and then implement the ATM example in chapter 14.

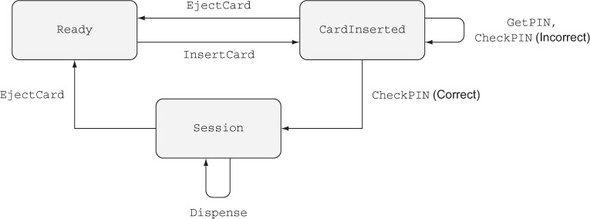

1.2.3. Concurrent programming

A concurrent program consists of multiple processes running at the same time and coordinating with each other. Concurrent programs can be responsive and continue to interact with a user while a large computation is running. For example, a user can continue browsing a web page while a large file is downloading. Moreover, by writing concurrent programs we can take full advantage of the processor power of modern CPUs, dividing work among multiple processes on separate CPU cores.

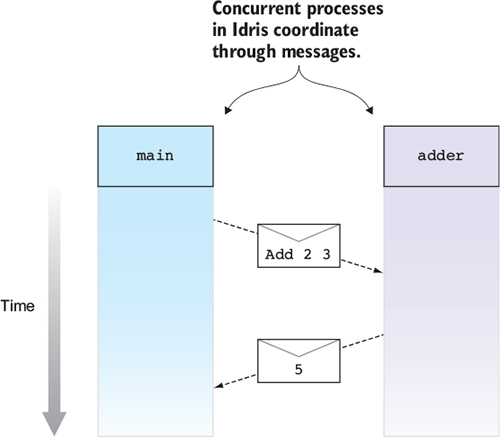

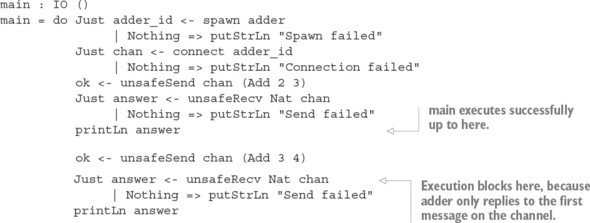

In Idris, processes coordinate with each other by sending and receiving messages. Figure 1.3 shows one way this can work, with two processes, main and adder. The adder process waits for a request to add numbers from other processes. After it receives a message from main asking it to add two numbers, it sends a response back with the result.

Figure 1.3. Two interacting concurrent processes, main and adder. The main process sends a request to adder, which then sends a response back to main.

Despite its advantages, however, concurrent programming is notoriously error prone. The need for processes to interact with each other can greatly increase a system’s complexity. For each process, you need to ensure that the messages it sends and

receives are properly coordinated with other processes. If, for example, main and adder aren’t properly coordinated and each is expecting to receive a message from the other at the same time, they’ll deadlock.Types versus testing for concurrent programs

Testing a concurrent program is difficult because, unlike a purely sequential program, there’s no guarantee about the order in which operations from different processes will execute. Even if two processes are correctly coordinated when you run a test once, there’s no guarantee they’ll be correctly coordinated when you next run the test. On the other hand, if you can express the coordination between processes in types, you can be sure that a concurrent program that type-checks has properly coordinated processes.

When you write concurrent programs, you’ll ideally have a model of how processes should interact. Using types, you can make this model explicit in code. Then, if a concurrent program type-checks, you’ll know that it correctly follows the model. In particular, you can do two things:

- Define an interface for adder that describes the form of messages it will handle.

- Define a protocol that defines the order of message passing, ensuring that main will always send a message to adder and then receive a reply, and adder will always do the opposite.

Concurrent programming is an extensive topic, and there are several ways you can use types to model coordination between processes. We’ll look at one example of how to do this in chapter 15.

1.2.4. Type, define, refine: the process of type-driven development

In each of these introductory examples, we’ve discussed in general terms how we might model a system: by describing the valid forms of inputs and outputs for matrix operations, the valid states of an interactive system, or the order of transmission of messages between concurrent processes. In each case, to implement the system, you start by trying to find a type that captures the important details of the model, and then define functions to work with that type, refining the type as necessary.

To put it succinctly, you can characterize type-driven development as an iterative process of type, define, refine: writing a type, implementing a function to satisfy that type, and refining the type or definition as you learn more about the problem.

With matrix addition, for example, you do the following:

- Type— Write a Matrix data type, and use it as the input and output types for an addition function.

- Define— Write an addition function that satisfies its input and output types.

- Refine— Notice that the input and output types for your addition function allow you to give invalid inputs with different dimensions, and then make the type more precise by including the dimensions of the matrices.

1.2.5. Dependent types

In the matrix arithmetic example, we began with a Matrix type and then refined it to include the number of rows and columns. This means, for example, that Matrix 3 4 is the type of 3 × 4 matrices. In this type, 3 and 4 are ordinary values. A dependent type, such as Matrix, is a type that’s calculated from some other values. In other words, it depends on other values.

By including values in a type like this, you can make types as precise as required. For example, some languages have a simple list type, describing lists of objects. You can make this more precise by parameterizing over the element type: a generic list of strings is more precise than a simple list and differs from a list of integers. You can be more precise still with a dependent type: a list of 4 strings differs from a list of 3 strings.

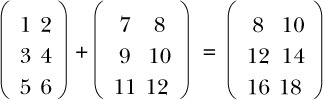

Table 1.2 illustrates how types in Idris can have differing levels of precision even for fundamental operations such as appending lists. Suppose you have two specific input lists of strings:

["a", "b", "c", "d"] ["e", "f", "g"]

Table 1.2. Appending specific typed lists. Unlike simple types, where there’s no difference between the input and output list types, dependent types allow the length to be encoded in the type.

| Input ["a", "b", "c", "d"] | Input ["e", "f", "g"] | Output type | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple | AnyList | AnyList | AnyList |

| Generic | List String | List String | List String |

| Dependent | Vect 4 String | Vect 3 String | Vect 7 String |

When you append them, you’ll expect the following output list:

["a", "b", "c", "d", "e", "f", "g"]

Using a simple type, both input lists have type AnyList, as does the output list. Using a generic type, you can specify that the input lists are both lists of strings, as is the output list. The more-precise types mean that, for example, the output is clearly related to the input in that the element type is unchanged. Finally, using a dependent type, you can specify the sizes of the input and output lists. It’s clear from the type that the length of the output list is the sum of the lengths of the input lists. That is, a list of 3 strings appended to a list of 4 strings results in a list of 7 strings.

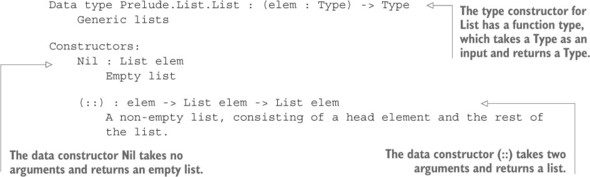

Lists and vectors

The syntax for the types in table 1.2 is valid Idris syntax. Idris provides several ways of building list types, with varying levels of precision. In the table, you can see two of these, List and Vect. AnyList is included in the table purely for illustrative purposes and is not defined in Idris. List encodes generic lists with no explicit length, and Vect (short for “vector”) encodes lists with the length explicitly in the type. You’ll see much more of both these types throughout this book.

Table 1.3 illustrates how the input and output types of an append function can be written with increasing levels of precision in Idris. Using simple types, you can write the input and output types as AnyList, suggesting that you have no interest in the types of the elements of the list. Using generic types, you can write the input and output types as List elem. Here, elem is a type variable standing for the element types. Because the type variable is the same for both inputs and the output, the types specify that both the input lists and the output list have a consistent element type. If you append two lists of integers, the types guarantee that the output will also be a list of integers. Finally, using dependent types, you can write the inputs as Vect n elem and Vect m elem, where n and m are variables representing the length of each list. The output type specifies that the resulting length will be the sum of the lengths of the inputs.

Table 1.3. Appending typed lists, in general. Type variables describe the relationships between the inputs and outputs, even though the exact inputs and outputs are unknown.

| Input 1 type | Input 2 type | Output type | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple | AnyList | AnyList | AnyList |

| Generic | List elem | List elem | List elem |

| Dependent | Vect n elem | Vect m elem | Vect (n + m) elem |

Type variables

Types often contain type variables, like n, m, and elem in table 1.3. These are very much like parameters to generic types in Java or C#, but they’re so common in Idris that they have a very lightweight syntax. In general, concrete type names begin with an uppercase letter, and type variable names begin with a lowercase letter.

In the dependent type for the append function in table 1.3, the parameters n and m are ordinary numeric values, and the + operator is the normal addition operator. All of these could appear in programs just as they’ve appeared here in the types.

Introductory exercises

Throughout this book, exercises will help reinforce the concepts you’ve learned. As a warm-up, take a look at the following selection of function specifications, given purely in the form of input and output types. For each of them, suggest possible operations

that would satisfy the given input and output types. Note that there could be more than one answer in each case.- Input type: Vect n elem Output type: Vect n elem

- Input type: Vect n elem Output type: Vect (n * 2) elem

- Input type: Vect (1 + n) elem Output type: Vect n elem

- Assume that Bounded n represents a number between zero and n - 1. Input types: Bounded n, Vect n elem Output type: elem

1.3. Pure functional programming

Idris is a pure functional programming language, so before we begin exploring Idris in depth, we should look at what it means for a language to be functional, and what we mean by the concept of purity. Unfortunately, there’s no universally agreed-on definition of exactly what it means for a programming language to be functional, but for our purposes we’ll take it to mean the following:

- Programs are composed of functions.

- Program execution consists of the evaluation of functions.

- Functions are a first-class language construct.

This differs from an imperative programming language primarily in that functional programming is concerned with the evaluation of functions, rather than the execution of statements.

In a pure functional language, the following are also true:

- Functions don’t have side effects such as modifying global variables, throwing exceptions, or performing console input or output.

- As a result, for any specific inputs, a function will always give the same result.

You may wonder, very reasonably, how it’s possible to write any useful software under these constraints. In fact, far from making it more difficult to write realistic programs, pure functional programming allows you to treat tricky concepts such as state and exceptions with the respect they deserve. Let’s explore further.

1.3.1. Purity and referential transparency

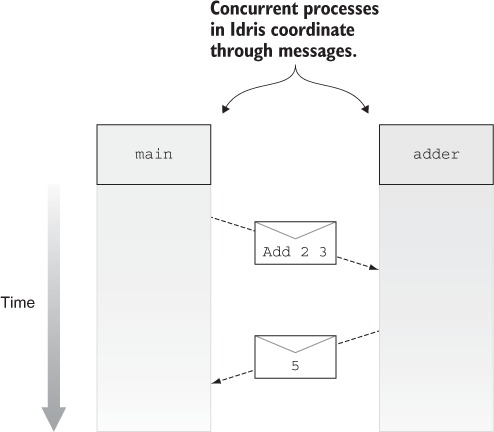

The key property of a pure function is that the same inputs always produce the same result. This property is known as referential transparency. An expression (such as a function call) in a function is referentially transparent if it can be replaced with its result without changing the behavior of the function. If functions produce only results, with no side effects, this property is clearly true. Referential transparency is a very useful concept in type-driven development, because if a function has no side effects and is

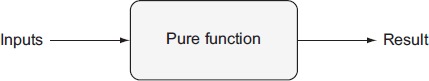

defined entirely by its inputs and outputs, then you can look at its input and output types and have a clear idea of the limits of what the function can do.Figure 1.4 shows example inputs and outputs for the append function. It takes two inputs and produces a result, but there’s no interaction with a user, such as reading from the keyboard, and no informative output, such as logging or progress bars.

Figure 1.4. A pure function, taking inputs and producing outputs with no observable side effects

Figure 1.5 shows pure functions in general. There can be no observable side effects when running these programs, other than perhaps making the computer slightly warmer or taking a different amount of time to run.

Figure 1.5. Pure functions, in general, take only inputs and have no observable side effects.

Pure functions are very common in practice, particularly for constructing and manipulating data structures. It’s possible to reason about their behavior because the function always gives the same result for the same inputs; these functions are important components of larger programs. The preceding append function is pure, and it’s a valuable component for any program that works with lists. It produces a list as a result, and because it’s pure, you know that it won’t require any input, output any logging, or do anything destructive like delete files.

1.3.2. Side-effecting programs

Realistically, programs must have side effects in order to be useful, and you’re always going to have to deal with unexpected or erroneous inputs in practical software. At first, this would seem to be impossible in a pure language. There is a way, however: pure functions may not be able to perform side effects, but they can describe them.

Consider a function that reads two lists from a file, appends them, prints the resulting list, and returns it. The following listing outlines this function in imperative-style pseudocode, using simple types.

Listing 1.1. Appending lists read from a file (pseudocode)

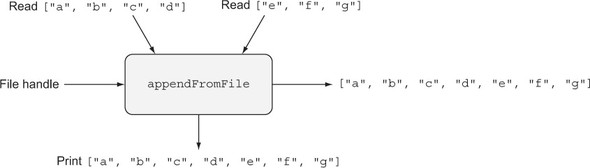

List appendFromFile(File h) { list1 = readListFrom(h) list2 = readListFrom(h) result = append(list1, list2) print(result) return result } This program takes a file handle as an input and returns a List with some side effects. It reads two lists from the given file and prints the list before returning. Figure 1.6 illustrates this for the situation when the file contains the two lists ["a", "b", "c", "d"] and ["e", "f", "g"].

Figure 1.6. A side-effecting program, reading inputs from a file, printing the result, and returning the result

The appendFromFile function doesn’t satisfy the referential transparency property. Referential transparency requires that an expression can be replaced by its result without changing the program’s behavior. Here, however, replacing a call to appendFromFile with its result means that nothing will be read from the file, and nothing will be output to the screen. The function’s input and output types tell us that the input is a file and the output is a list, but nothing in the type describes the side effects the function may execute.

In pure functional programming in general, and Idris in particular, you can solve this problem by writing functions that describe side effects, rather than functions that execute them, and defer the details of execution to the compiler and runtime system. We’ll explore this in greater detail in chapter 5; for now, it’s sufficient to recognize that a program with side effects has a type that makes this explicit. For example, there’s a distinction between the following:

- String is the type of a program that results in a String and is guaranteed to perform no input or output as side effects.

- IO String is the type of a program that describes a sequence of input and output operations that result in a String.

Type-driven development takes this idea much further. As you’ll see from chapter 12 onward, you can define types that describe the specific side effects a program can have, such as console interaction, reading and writing global state, or spawning concurrent processes and sending messages.

1.3.3. Partial and total functions

Idris supports an even stronger property than purity for functions, making a distinction between partial and total functions. A total function is guaranteed to produce a result, meaning that it will return a value in a finite time for every possible well-typed input, and it’s guaranteed not to throw any exceptions. A partial function, on the other hand, might not return a result for some inputs. Here are a couple of examples:- The append function is total for finite lists, because it will always return a new list.

- The function that returns the first element of a list is partial, because it’s not defined if the list is empty, and it will therefore crash.

Total functions and long-running programs

A total function is guaranteed to produce a finite prefix of a potentially infinite result. As you’ll see in chapter 11, you can write command shells or servers as total functions that guarantee a response for every user input, indefinitely.

The distinction is important because knowing that a function is total allows you to make much stronger claims about its behavior based on its type. If you have a function with a return type of String, for example, you can make different claims depending on whether the function is partial or total.

- If it’s total— It will return a value of type String in finite time.

- If it’s partial— If it doesn’t crash or enter an infinite loop, the value it returns will be a String.

In most modern languages, we must assume that functions are partial and can therefore only make the latter, weaker, claim. Idris checks whether functions are total, so we can therefore often make the former, stronger, claim.

The halting problem is the problem of determining whether a program terminates for some specific input. Thanks to Alan Turing, we know that it’s not possible to write a program that solves the halting problem in general. Given this, it’s reasonable to wonder how Idris can determine that a function is total, which is essentially checking that a function terminates for all inputs.

Although it can’t solve the problem in general, Idris can identify a large class of functions that are definitely total. You’ll learn more about how it does so, along with some techniques for writing total functions, in chapters 10 and 11.

A useful pattern in type-driven development is to write a type that precisely describes the valid states of a system (like the ATM in section 1.2.2) and that constrains the operations

the system is allowed to perform. A total function with that type is then guaranteed by the type checker to perform those operations as precisely as the type requires.1.4. A quick tour of Idris

The Idris system consists of an interactive environment and a batch mode compiler. In the interactive environment, you can load and type-check source files, evaluate expressions, search libraries, browse documentation, and compile and run complete programs. We’ll use these features extensively throughout this book.

In this section, I’ll briefly introduce the most important features of the environment, which are evaluation and type checking, and describe how to compile and run Idris programs. I’ll also introduce the two most distinctive features of the Idris language itself:

- Holes, which stand for incomplete programs

- The use of types as first-class language constructs

As you’ll see, by using holes you can define functions incrementally, asking the type checker for contextual information to help complete definitions. Using first-class types, you can be very precise about what a function is intended to do, and even ask the type checker to fill in some of the details of functions for you.

1.4.1. The interactive environment

Much of your interaction with Idris will be through an interactive environment called the read-eval-print loop, typically abbreviated as REPL. As the name suggests, the REPL will read input from the user, usually in the form of an expression, evaluate the expression, and then print the result.

Once Idris is installed, you can start the REPL by typing idris at a shell prompt. You should see something like the following:

____ __ _ / _/___/ /____(_)____ / // __ / ___/ / ___/ Version 1.0 _/ // /_/ / / / (__ ) http://www.idris-lang.org/ /___/\__,_/_/ /_/____/ Type :? for help Idris is free software with ABSOLUTELY NO WARRANTY. For details type :warranty. Idris>

Installing Idris

You can find instructions on how to download and install Idris for Linux, OS X, or Windows in appendix A.

You can enter expressions to be evaluated at the Idris> prompt. For example, arithmetic expressions work in the conventional way, with the usual precedence rules (that is, * and / have higher precedence than + and -):

Idris> 2 + 2 4 : Integer Idris> 2.1 * 20 42.0 : Double Idris> 6 + 8 * 11 94 : IntegerYou can also manipulate Strings. The ++ operator concatenates Strings, and the reverse function reverses a String:

Idris> "Hello" ++ " " ++ "World!" "Hello World!" : String Idris> reverse "abcdefg" "gfedcba" : String

Notice that Idris prints not only the result of evaluating the expression, but also its type. In general, if you see something of the form x : T—some expression x, a colon, and some other expression T—this can be read as “x has type T.” In the previous examples, you have the following:

- 4 has type Integer.

- 42.0 has type Double.

- "Hello World!" has type String.

1.4.2. Checking types

The REPL provides a number of commands, all prefixed by a colon. One of the most commonly useful is :t, which allows you to check the types of expressions without evaluating them:

Idris> :t 2 + 2 2 + 2 : Integer Idris> :t "Hello!" "Hello!" : String

Types, such as Integer and String, can be manipulated just like any other value, so you can check their types too:

Idris> :t Integer Integer : Type Idris> :t String String : Type

It’s natural to wonder what the type of Type itself might be. In practice, you’ll never need to worry about this, but for the sake of completeness, let’s take a look:

Idris> :t Type Type : Type 1That is, Type has type Type 1, Type 1 has type Type 2, and so on forever, as far as we’re concerned. The good news is that Idris will take care of the details for you, and you can always write Type alone.

1.4.3. Compiling and running Idris programs

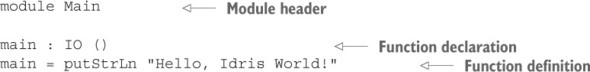

As well as evaluating expressions and inspecting the types of functions, you’ll want to be able to compile and run complete programs. The following listing shows a minimal Idris program.

Listing 1.2. Hello, Idris World! (Hello.idr)

At this stage, there’s no need to worry too much about the syntax or how the program works. For now, you just need to know that Idris source files consist of a module header and a collection of function and data type definitions. They may also import other source files.

Whitespace significance

Whitespace is significant in Idris, so when you type listing 1.2, make sure there are no spaces at the beginning of each line.

Here, the module is called Main, and there’s only one function definition, called main. The entry point to any Idris program is the main function in the Main module.

To run the program, follow these steps:

- Create a file called Hello.idr in a text editor.[1] Idris source files all have the extension .idr.

I recommend Atom because it has a mode for interactive editing of Idris programs, which we’ll use in this book.1 - Enter the code in listing 1.2.

- In the working directory where you saved Hello.idr, start up an Idris REPL with the command idris Hello.idr.

- At the Idris prompt, type :exec.

If all is well, you should see something like the following:

$ idris Hello.idr ____ __ _ / _/___/ /____(_)____ / // __ / ___/ / ___/ Version 1.0 _/ // /_/ / / / (__ ) http://www.idris-lang.org/ /___/\__,_/_/ /_/____/ Type :? for help Idris is free software with ABSOLUTELY NO WARRANTY. For details type :warranty. Type checking ./Hello.idr *Hello> :exec Hello, Idris WorldHere, $ stands for your shell prompt. Alternatively, you can create a standalone executable by invoking the idris command with the -o option, as follows:

$ idris Hello.idr -o Hello $ ./Hello Hello, Idris World

The REPL prompt

The REPL prompt, by default, tells you the name of the file that’s currently loaded. The Idris> prompt indicates that no file is loaded, whereas the prompt *Hello> indicates that the Hello.idr file is loaded.

1.4.4. Incomplete definitions: working with holes

Earlier, I compared working with types and values to inserting shapes into a shape-sorter toy. Much as the square shape will only fit through a square hole, the argument "Hello, Idris World!" will only fit into a function in a place where a String type is expected.

Idris functions themselves can contain holes, and a function with a hole is incomplete. Only a value of an appropriate type will fit into the hole, just as a square shape will only fit into a square hole in the shape sorter. Here’s an incomplete implementation of the “Hello, Idris World!” program:

If you edit Hello.idr to replace the string "Hello, Idris World!" with ?greeting and load it into the Idris REPL, you should see something like the following:

Type checking ./Hello.idr Holes: Main.greeting *Hello>

The syntax ?greeting introduces a hole, which is a part of the program yet to be written. You can type-check programs with holes and evaluate them at the REPL.

Here, when Idris encounters the ?greeting hole, it creates a new name, greeting, that has a type but no definition. You can inspect the type using :t at the REPL:

*Hello> :t greeting -------------------------------------- greeting : String

If you try to evaluate it, on the other hand, Idris will show you that it’s a hole:

*Hello> greeting ?greeting : String

Instead of exiting the REPL and restarting, you can also reload Hello.idr with the :r REPL command as follows:

*Hello> :r Type checking ./Hello.idr Holes: Main.greeting *Hello>

Holes allow you to develop programs incrementally, writing the parts you know and asking the machine to help you by identifying the types for the parts you don’t. For example, let’s say you’d like to print a character (with type Char) instead of a String. The putStrLn function requires a String argument, so you can’t simply pass a Char to it.

Listing 1.3. A program with a type error

If you try loading this program into the REPL, Idris will report an error:

Hello.idr:4:17:When checking right hand side of main: When checking an application of function Prelude.putStrLn: Type mismatch between Char (Type of 'x') and String (Expected type)

You have to convert a Char to a String somehow. Even if you don’t know exactly how to do this at first, you can start by adding a hole to stand in for a conversion.

module Main main : IO () main = putStrLn (?convert 'x')

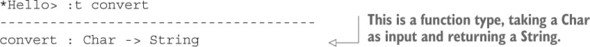

Then you can check the type of the convert hole:

The type of the hole, Char -> String, is the type of a function that takes a Char as an input and returns a String as an output. We’ll discuss type conversions in more detail in chapter 2, but an appropriate function to complete this definition is cast:

main : IO () main = putStrLn (cast 'x')

1.4.5. First-class types

A first-class language construct is one that’s treated as a value, with no syntactic restrictions on where it can be used. In other words, a first-class construct can be passed to functions, returned from functions, stored in variables, and so on.In most statically typed languages, there are restrictions on where types can be used, and there’s a strict syntactic separation between types and values. You can’t, for example, say x = int in the body of a Java method or C function. In Idris, there are no such restrictions, and types are first-class; not only can types be used in the same way as any other language construct, but any construct can appear as part of a type.

This means that you can write functions that compute types, and the return type of a function can differ depending on the input value to a function. This idea comes up regularly when programming in Idris, and there are several real-world situations where it’s useful:

- A database schema determines the allowed forms of queries on a database.

- A form on a web page determines the number and type of inputs expected.

- A network protocol description determines the types of values that can be sent or received over a network.

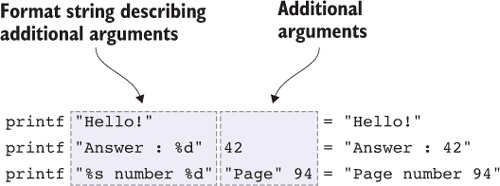

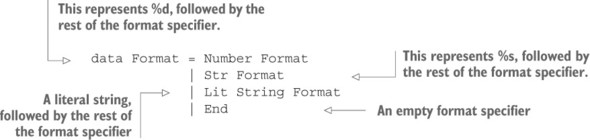

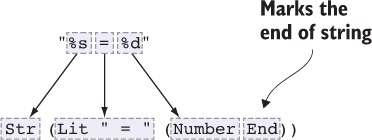

In each of these cases, one piece of data tells you about the expected form of some other data. If you’ve programmed in C, you’ll have seen a similar idea with the printf function, where one argument is a format string that describes the number and expected types of the remaining arguments. The C type system can’t check that the format string is consistent with the arguments, so this check is often hardcoded into C compilers. In Idris, however, you can write a function similar to printf directly, by taking advantage of types as first-class constructs. You’ll see this specific example in chapter 6.

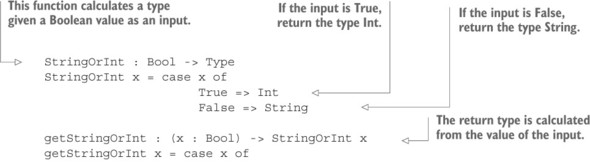

The following listing illustrates the concept of first-class types with a small example: computing a type from a Boolean input.

Listing 1.4. Calculating a type, given a Boolean value (FCTypes.idr)

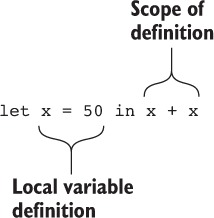

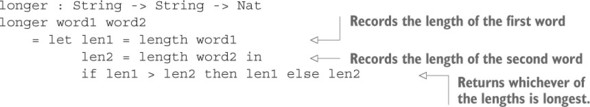

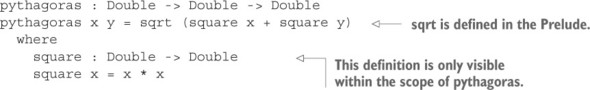

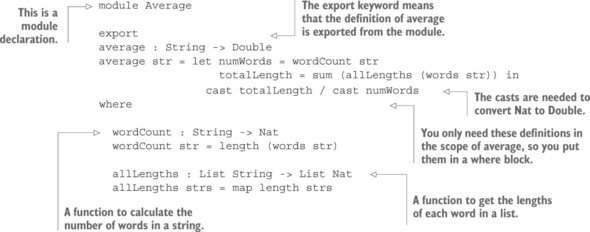

We’ll go into much more detail on Idris syntax in the coming chapters. For now, just keep the following in mind:

- A function type takes the form a -> b -> ... -> t, where a, b, and so on, are the input types, and t is the output type. Inputs may also be annotated with names, taking the form (x : a) -> (y : b) -> ... -> t.

- name : type declares a new function, name, of type type.

- Functions are defined by equations: square x = x * x

This defines a function called square that multiplies its input by itself

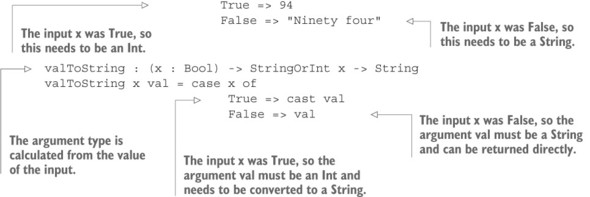

Here, StringOrInt is a function that computes a type. Listing 1.4 uses it in two ways:

- In getStringOrInt, StringOrInt calculates the return type. If the input is True, getStringOrInt returns an Int; otherwise it returns a String.

- In valToString, StringOrInt calculates an argument type. If the first input is True, the second input must be an Int; otherwise it must be a String.

You can see in detail what’s going on by introducing holes in the definition of valToString:

valToString : (x : Bool) -> StringOrInt x -> String valToString x val = case x of True => ?xtrueType False => ?xfalseType

Inspecting the type of a hole with :t gives you not only the type of the hole itself, but also the types of any local variables in scope. If you check the type of xtrueType, you’ll see the type of val, which is computed when x is known to be True:

*FCTypes> :t xtrueType x : Bool val : Int -------------------------------------- xtrueType : String

So, if x is True, then val must be an Int, as computed by the StringOrInt function. Similarly, you can check the type of xfalseType to see the type of val when x is known to be False:

*FCTypes> :t xfalseType x : Bool val : String -------------------------------------- xfalseType : String

This is a small example, but it illustrates a fundamental concept of type-driven development and programming with dependent types: the idea that the type of a variable can be computed from the value of another. In each case, Idris has used StringOrInt to refine the type of val, given what it knows about the value of x.

1.5. Summary

- Types are a means of classifying values. Programming languages use types to decide how to lay out data in memory, and to ensure that data is interpreted consistently.

- A type can be viewed as a specification, so that a language implementation (specifically, its type checker) can check whether a program conforms to that specification.

- Type-driven development is an iterative process of type, define, refine, creating a type to model a system, then defining functions, and finally refining the types as necessary.

- In type-driven development, a type is viewed more like a plan, helping an interactive environment guide the programmer to a working program.

- Dependent types allow you to give more-precise types to programs, and hence more informative plans to the machine.

- In a functional programming language, program execution consists of evaluating functions.

- In a purely functional programming language, additionally, functions have no side effects.

- Instead of writing programs that perform side effects, you can write programs that describe side effects, with the side effects stated explicitly in a program’s type.

- A total function is guaranteed to produce a result for any well-typed input in finite time.

- Idris is a programming language that’s specifically designed to support type-driven development. It’s a purely functional programming language with first-class dependent types.

- Idris allows programs to contain holes that stand for incomplete programs.

- In Idris, types are first-class, meaning that they can be stored in variables, passed to functions, or returned from functions like any other value.

Chapter 2. Getting started with Idris

This chapter covers

- Using built-in types and functions

- Defining functions

- Structuring Idris programs

When learning any new language, it’s important to have a solid grasp of the fundamentals before moving on to the more distinctive features of the language. With this in mind, before we begin exploring dependent types and type-driven development itself, we’ll look at some types and values that will be familiar to you from other languages, and you’ll see how they work in Idris. You’ll also see how to define functions and put these together to build a complete, if simple, Idris program.

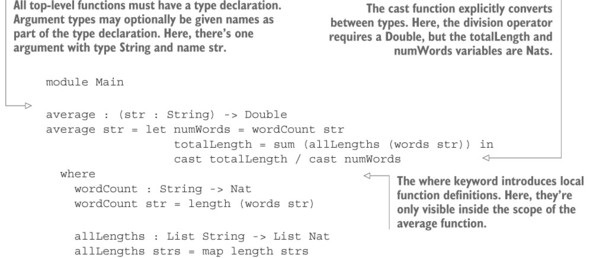

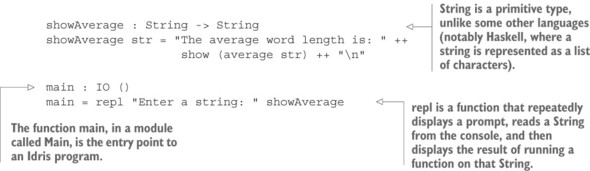

If you’re already familiar with a pure functional language, particularly Haskell, much of this chapter will seem very familiar. Listing 2.1 shows a simple, but self--contained, Idris program that repeatedly prompts for input from the console and then displays the average length of the words in the input. If you’re already comfortable reading this program with the help of the annotations, you can safely skip this chapter, as it deliberately avoids introducing any language features specific to Idris.[1]

Even so, I still suggest you browse through this chapter’s tips and notes and read the summary at the end to make sure there aren’t any small details you’ve missed.Comparing Idris to Haskell, the most important difference is that Idris doesn’t use lazy evaluation by default.

1

Otherwise, don’t worry. By the end of this chapter we’ll have covered all of the necessary features for you to be able to implement similar programs yourself.

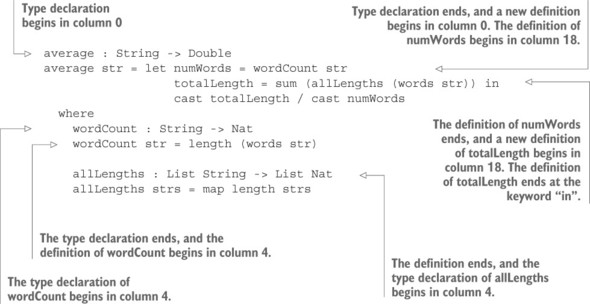

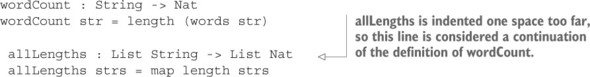

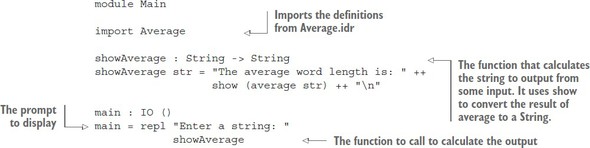

Listing 2.1. A complete Idris program to calculate average word length (Average.idr)

2.1. Basic types

Idris provides some standard basic types and functions for working with various forms, characters, and strings. In this section, I’ll give you an overview of these, along with some examples. These basic types are defined in the Prelude, which is a collection of standard types and functions automatically imported by every Idris program.

I’ll show you several example expressions in this section, and it may seem fairly clear what they should do. Nevertheless, instead of simply reading them and nodding, I strongly recommending you type the examples at the Idris REPL. You’ll learn the syntax much more easily by using it than you will by merely reading it.

Along the way, we’ll also encounter a couple of useful REPL features that will allow us to store the results of calculations at the REPL.

The Prelude

The types and functions I’ll discuss are defined in the Prelude. The Prelude is Idris’s standard library, always available at the REPL and automatically imported by every Idris program. With the exception of some primitive types and operations, everything in the Prelude is written in Idris itself.2.1.1. Numeric types and values

Idris provides several basic numeric types, including the following:

- Int—A fixed-width signed integer type. It’s guaranteed to be at least 31 bits wide, but the exact width is system dependent.

- Integer—An unbounded signed integer type. Unlike Int, there’s no limit to the size of the numbers that can be represented, other than your machine’s memory, but this type is more expensive in terms of performance and memory usage.

- Nat—An unbounded unsigned integer type. This is very often used for sizes and indexing of data structures, because they can never be negative. You’ll see much more of Nat later.

- Double—A double-precision floating-point type.

Subtraction with Nats

Because Nats can never be negative, a Nat can only be subtracted from a larger Nat.

We can use standard numeric literals as values for each of these types. For example, the literal 333 can be of type Int, Integer, Nat, or Double. The literal 333.0 can be only of type Double, due to the explicit decimal point.

You can try some simple calculations at the REPL:

Idris> 6 + 3 * 12 42 : Integer Idris> 6.0 + 3 * 12 42.0 : Double

Note that Idris will treat a number as an Integer by default, unless there’s some context, and both operands must be the same type. Therefore, in the second of the two preceding expressions, the literal 6.0 can be only a Double, so the whole expression is a Double, and 3 and 12 are also treated as Doubles.

The most recent result at the REPL can always be retrieved and used in further calculations by using the special value it:

Idris> 6 + 3 * 12 42 : Integer Idris> it * 2 84 : Integer

It’s also possible to bind expressions to names at the REPL using the :let command:

Idris> :let x = 100 Idris> x 100 : Integer Idris> :let y = 200.0 Idris> y 200.0 : Double

When an expression, such as 6 + 3 * 12, can be one of several types, you can make the type explicit with the notation the <type><expression>, to say that type is the required type of expression:

Idris> 6 + 3 * 12 42 : Integer Idris> the Int (6 + 3 * 12) 42 : Int Idris> the Double (6 + 3 * 12) 42.0 : Double